A distant reading 7th-12th century seals from the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Seal Online Catalogue

Paul Albert

12/6/21

Introduction

This paper discusses work in progress examining the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Seal Online Catalogue[1]. The Catalogue describes seals used by people of the Byzantine empire with their written correspondence. For this project, a subset of 13,600 unique Byzantine seals from the Catalogue’s 15,100 seals[2] was examined. Not only is this a large subset of seals in the catalogue, but it is also a significant subset of seals known to exist today (estimates of this number range from 80,000[3] – 100,000[4]).

Byzantine seals had the utilitarian functions of securing documents and authenticating the sender[5], but they also had numerous emotive functions as well[6]. In this regard, a common comparison is made between these seals and modern-day business cards.[7] Certainly, a modern business card is expected to give utilitarian information about a person (company, title, contact information, etc.), but it is also expressly designed to carry along with it certain emotive signals as well. The weight of the card stock, the selection of font, the possible inclusion of photos, slogans, mission statements, etc. are all meant to convey an emotive signal about some important essence of the card bearer.[8]

From this perspective, a longitudinal study of Byzantine seals can offer us a unique window into Byzantine culture and the individuals within it; a glimpse into general trends both in overall cultural conventions and individual aspirations. Taken as a whole, the seals allow a unparalled window into examining many facets of Byzantine culture and society.

With a few notable exceptions[9], past examinations of Byzantine seals have usually focused on only a small set of seal exemplars for analysis. The goal of this paper is different. Rather than focus on a small set of seals, this paper seeks to look at patterns that exist among the whole through a “distant reading” approach.

By “distant reading,” I refer to the theoretical approach popularized by Franco Moretti[10] to use computational analysis to describe regularities and differences found in textual corpuses. In this specific project, the corpus of text examined includes the text directly inscribed on the seal itself, as well as the text used by Dumbarton Oaks in the catalogue to describe the obverses (front) and reverses (back) of the seals.

“Capta” not “Data”

In discussing the nature of information analyzed in the Digital Humanities, Johanna Drucker popularized the idea of using the term “capta” rather than “data” to describe the type information this paper studies. Drucker points out that there is a phenomenological distinction between information that might be recorded by an instrument (such as size, weight, metallic composition, etc.) and types of information that are constructed by human interpretation. She states:

Capta is “taken” actively while data is assumed to be a “given” able to be recorded and observed. From this distinction, a world of differences arises. Humanistic inquiry acknowledges the situated, partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production, the recognition that knowledge is constructed, taken, not simply given as a natural representation of pre-existing fact.[11]

While the present paper somewhat blithely presents figures in a way that might make lead the reader to think of the information being analyzed as being clear cut and binary, I hope the reader keeps in mind that information being analyzed has many levels of ambiguity and human interpretation.

For example, even something as seemingly clear cut as the century of the date of a seal should belong to depends highly on human interpretation.[12] With the small exception of seals for emperors or other notable persons (where specific years are certain), the process of ascribing a date range to a seal is inherently a subjective exercise. All told, only about 5% of the 13,600 unique seals used in this project have enough information for specific years to be assigned to a seal. For the other 95% of the seals, where only a range of centuries could be estimated, the cataloguers at Dumbarton Oaks look at many seal features but most closely at the epigraphy of inscribed text (see Footnote ).

Further ambiguities in our information arise from the specific vagaries in the cataloguing process itself and the seals themselves. The Online Catalogue built by Dumbarton Oaks is the product of many hands across many years (as are the seals it describes). For example, there are various ways of marking a saint (“Saint,” “St.” or “St ”), various ways of marking the Virgin Mary (“Virgin,” “Mother of God,” “Theotokis,” etc.), various ways of marking Christ (“Lord,” “Christ,” “Savior,” etc.) that differ between the various seals and fields in the catalog. While these “fuzzy” differences are easily understood by the human reader, the differences need to be identified and reconciled for a computational analysis seeking patterns between the seals.

Further ambiguities in the information studied arise from the nature in which the information was coded and captured through “web scraping.” For example, different practices are used in the Catalogue in distinguishing Greek text from its English translation. While these distinctions seem perfectly clear to the viewer of the Online Catalogue, they do pose problems for a “web scraper” seeking to categorize the information scraped from a web page.

“So, what is the point?” you, the reader, might be asking. If this information is inherently challenged, why spend time analyzing it? Ontologically, I would argue, this Digital Humanities project does exactly what historians have always done, look at anecdotal pieces of information, seek out patterns and draw conclusions. One can even argue that a Digital Humanities project forces the scholar to recognize ambiguities in information that are routinely overlooked when information is not forced into becoming numbers.

Still, to avoid the reader unconsciously assuming a false exactitude, this paper will generally round percentages, use thick translucent lines in charts rather than thin opaque lines and stay away from the word “data” and use the term “information” to describe what is being analyzed.

While we need to begin with a firm recognition that we are dealing with “capta” and not “data” for this analysis, there are sufficient regularities in the information compiled and captured from the catalogue to allow for some general patterns to be analyzed. The fact that we are dealing with a relatively large number of items here gives some comfort that while all the nuances of each seal might not be perfectly captured in the binary nature of a computational approach, there is enough information that possesses enough regularities for some general conclusions to be reliably drawn.[13]

To help with the reader further explore my analysis, I have built an online interactive dashboard where my findings can be explored. The dashboard allows the user to explore aggregate patterns (the whole) as well as explore the images and captured information from the individual seals that form these patterns (the parts). [A preliminary version can be found here, it is my hope that Dumbarton Oaks will soon modify its web server settings to allow for the images of seal obverse and reverse to be displayed interactively on the dashboard.]

Analytical Approach

For this project, I only look at a subset of online catalogue seals that have been ascribed to the 7th through 12th centuries, are noted to have been in Greek or Latin languages and presented usable text for the various fields used in my analysis. All told, this is a set of 13,600 unique seals.

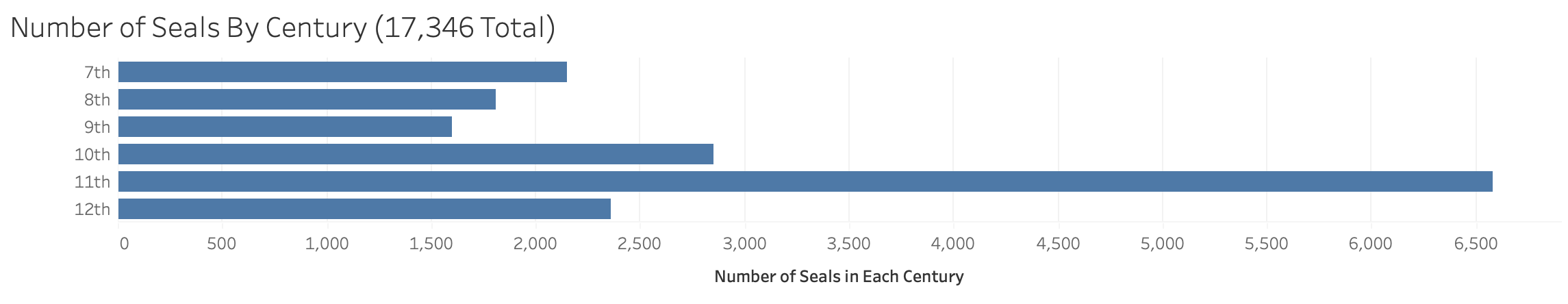

To capture the ambiguous nature of the century a seal might belong to, I have decided to count seals for every century they have been attributed to. If a seal is listed as both 8th and 9th century, then this analysis will count that seal for both centuries. Roughly 45% of the seals are listed for two centuries (a few of these had specific dates such as such as BZS.1947.2.344 “Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118),” but the vast majority had a much more general dating such as BZS.1947.2.344 “Heliobos monk (tenth/eleventh century).” By (double) counting these seals across each century in the multiple centuries attributed, we obtain a set of 17,346 unique records from our 13,600 unique seals

Figure . Number of seals by century attribution from Dumbarton Oaks online catalogue selected for project analysis. 13,600 unique seals, 17,346 unique records when counted by century attribution (for example, a seal ascribed to both the 10th and 11th century is counted in both centuries).

In general, three different information fields from the online catalogue were developed and analyzed for this project.

- Inscribed Text Field – the text inscribed on the seal (contains the Greek/Latin text with English translation). It was often a practice in seals to use abbreviations in the actual words inscribed on a seal. One example from this field would be – “Christ, help your servant Stephen.”

- Obverse Description Field – an English description of what the obverse (front) of the seal shows. One example from this field would be – “Bust of St. Michael holding scepter with trefoil and globe. Border of dots.”

- Reverse Description Field – an English description of what the reverse (back) of the seal shows. One example from this field would be – “Inscription of seven lines within linear border. Border of dots.”

Key Findings

Overall, 70% of the seals studied go beyond giving utilitarian information about the sender to also include explicit written invocations seeking divine assistance to directly benefit the sender (for example, “Lord, help Theodore, notarios”). As an emotive signal, such an invocation could signal the piety (and trustworthiness) of the sender. From the sender’s individual standpoint, such an invocation might also have been intended as a “living prayer” to be echoed and reinforced every time the seal was read by its receiver.

As can be seen in , these invocations were made to different divine beings and the explicit terms used seeking of assistance varied.

Sample Inscribed Text Field entries considered to explicitly invoke divine assistance:

|

Lord, help your servant Leo. |

|

Lord, help Andronikos, sebastokrator, born in the purple. |

|

(Lord, help) Theophylaktos Synadenos. |

|

Martyr, may you protect Manuel Komnenodoukas. |

|

All holy One, may you protect the owner of this letter. |

|

Forerunner, watch over John Trichas. |

|

Jesus Christ, King of Kings. Mother of God, help John, despotes. |

|

May you, Virgin, protect Eumathios Philokales, doux and protonobellisimos. |

|

Mother of God, help your servant Constantine. |

|

Theotokos, help Constantine Loupos, dishypatos. |

Table . Examples of seals where inscribed text explicitly invoked divine assistance.

Seals of the 8th – 10th centuries most characteristically invoked divine assistance

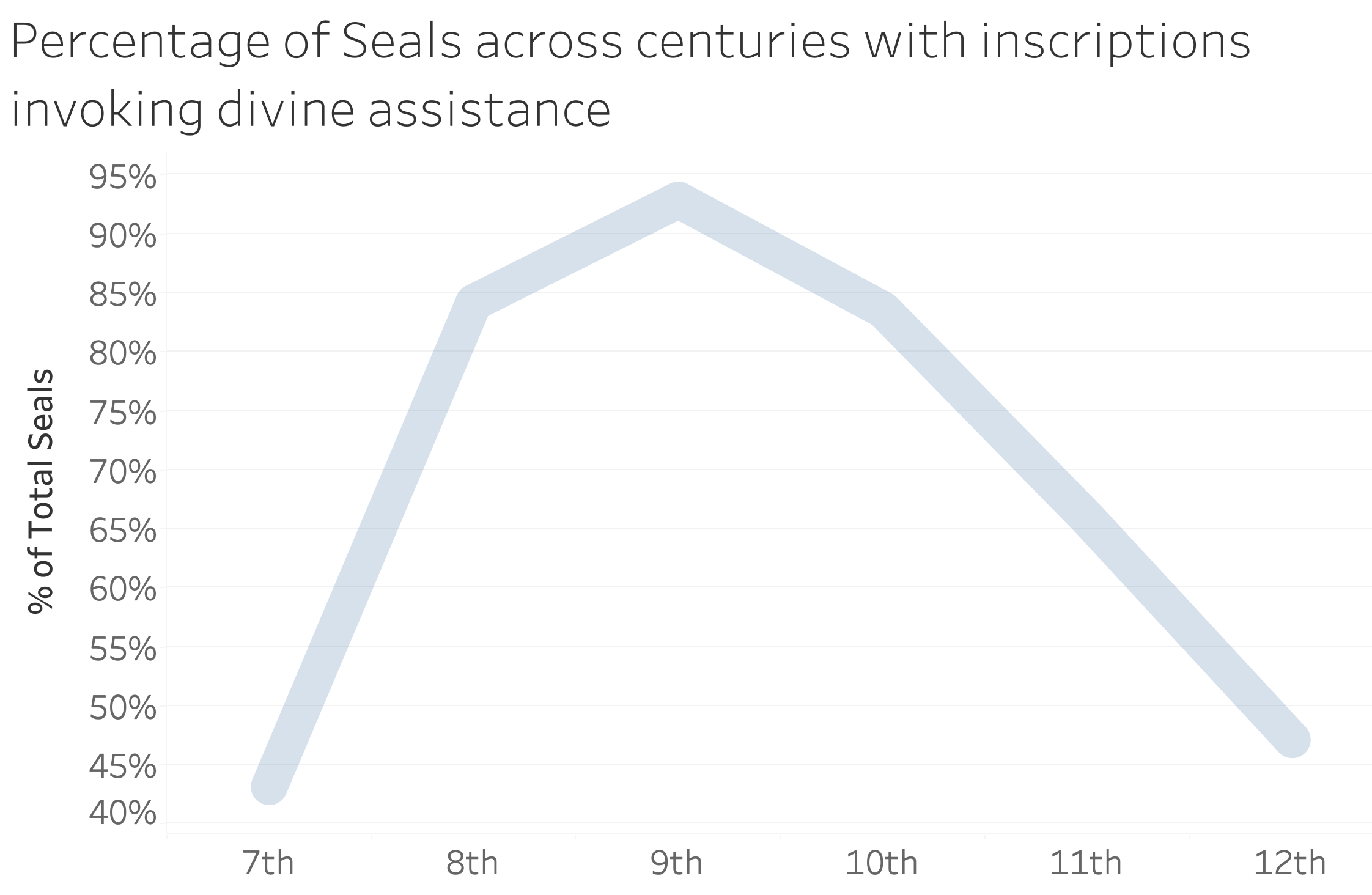

Across the seal records examined, a clear trend of the percentage of seals for each century that invoke divine assistance in the Inscribed Text Field.[14]

Figure . Percentage of seals invoking divine assistance shows remarkable change across time

Starting in the 7th century, less than 50% of our seals expressly sought divine assistance in their text inscriptions. However, by the 9th century, that percentage rose to over 90, decreasing to less than 50% by the 12th century (see ).

The main phenomenon this paper seeks to explore is the startling conformity of 9th century seals to explicitly invoke divine assistance for the seal owner. First, we examine other seal characteristics that might correlate with this practice. Next, we discuss some ideas about why this practice might have existed.

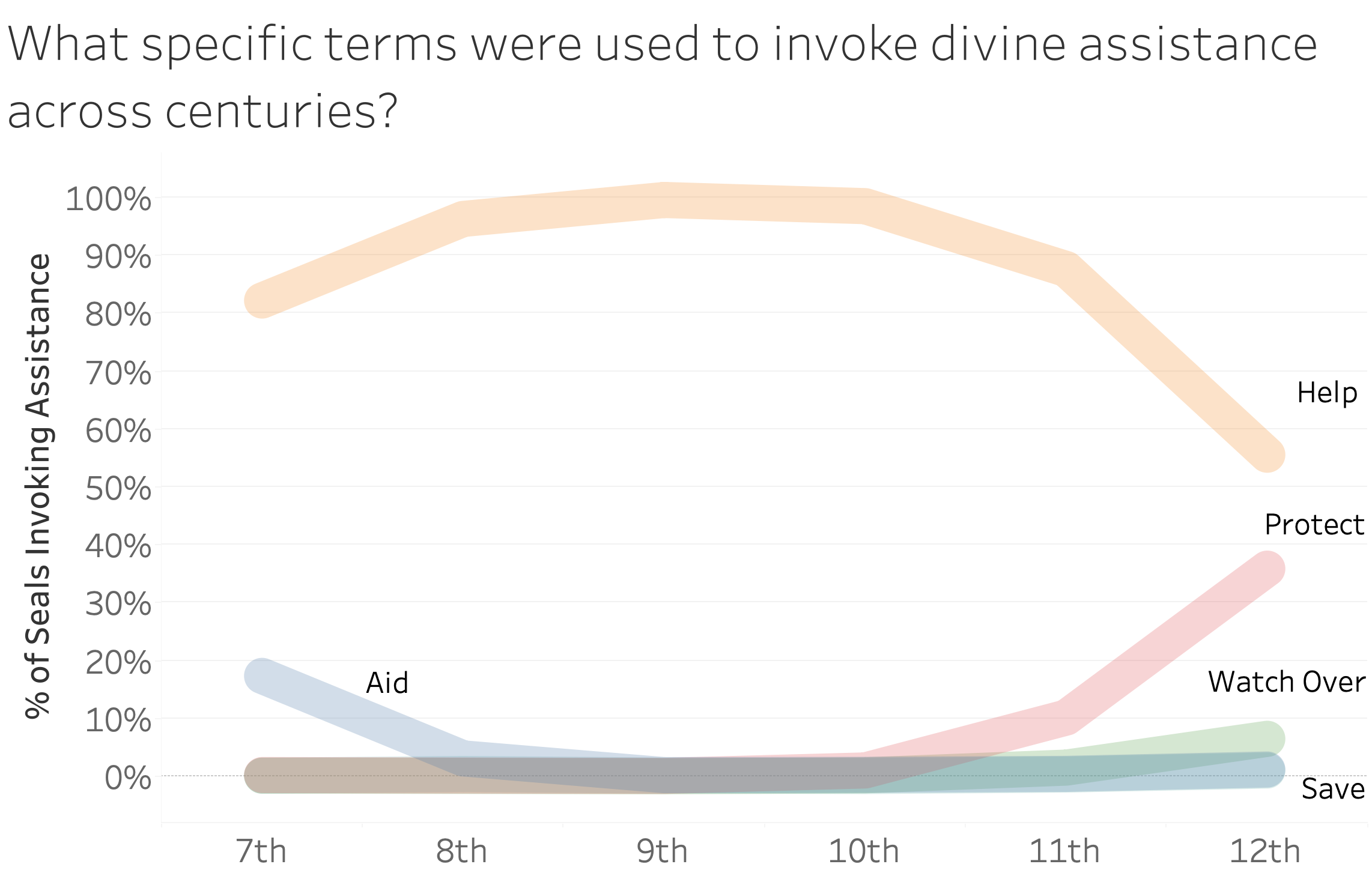

Seals expressly invoking divine assistance mostly used the term “Help” (βοήθει)

While the seals of the 9th century, compared to other centuries, show striking conformities in invoking divine assistance, they mostly seek the same form of assistance as seals from other centuries. Specifically, the explicit term used for the type of assistance sought is generally the word “help” (βοήθει). The biggest change in terms used was in the 12th century where a sizable portion of the seals (about 40%) invoking divine assistance adopt the term “Protect” (σκέποις). See Figure 3.

Figure . Percentage of terms used in invoking divine aid (Inscribed Text Field)

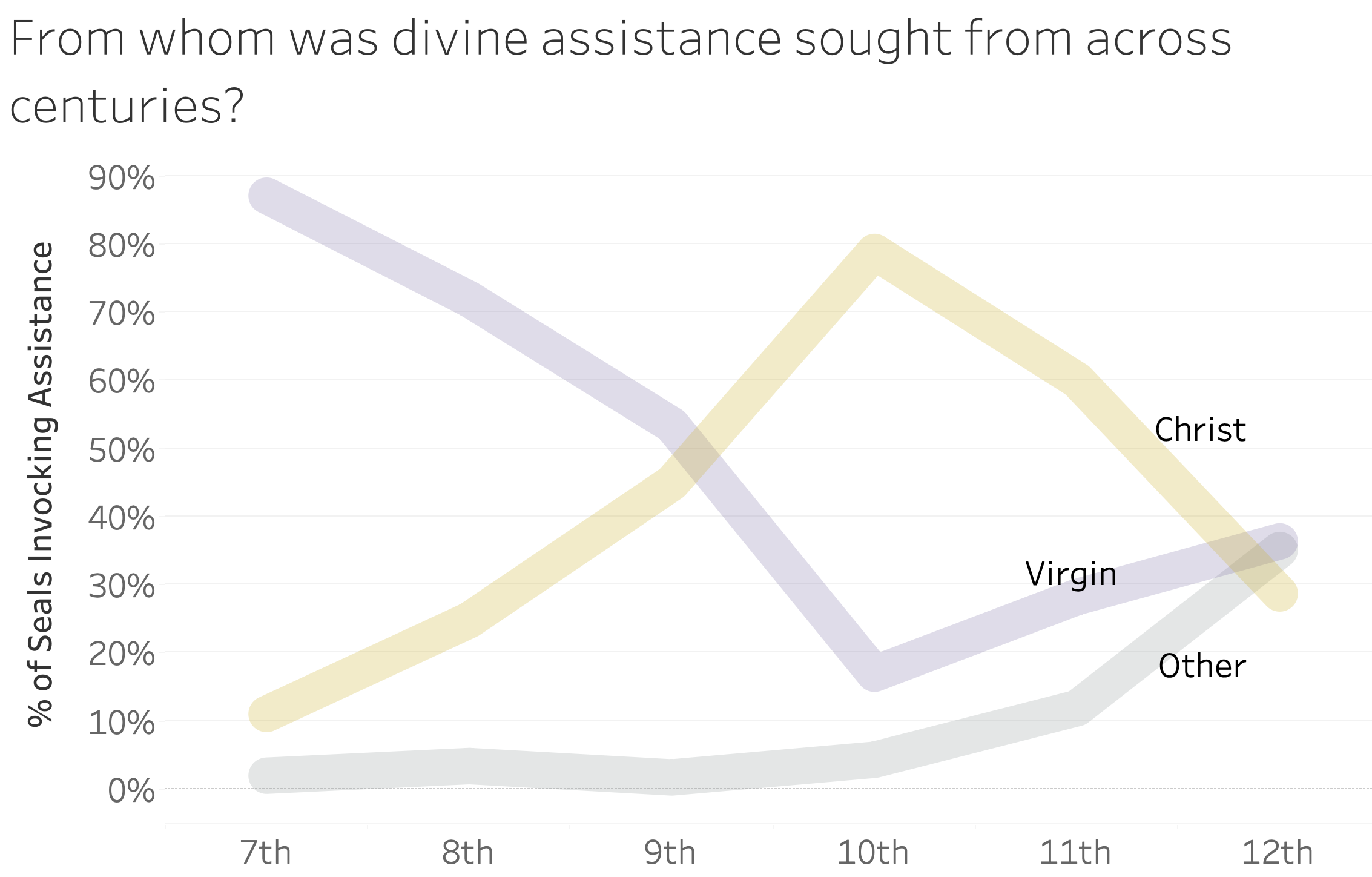

Who help is sought from changes over the centuries

While over 90% of our 9th century seals expressly invoke divine assistance, those that do seek help are split in seeking help from the Virgin or Christ. In contrast, seals of the 7th century almost entirely seek help from the Virgin.[15] See .

Figure . Who was help sought from? Divine entity appealed to by invocations in Interpreted Text Field.

Starting in the 11th century there is a marked increase in seeking divine help from other than Christ or the Virgin. Usually, if not Christ or the Virgin, the divine entity invoked is a Saint.[16]

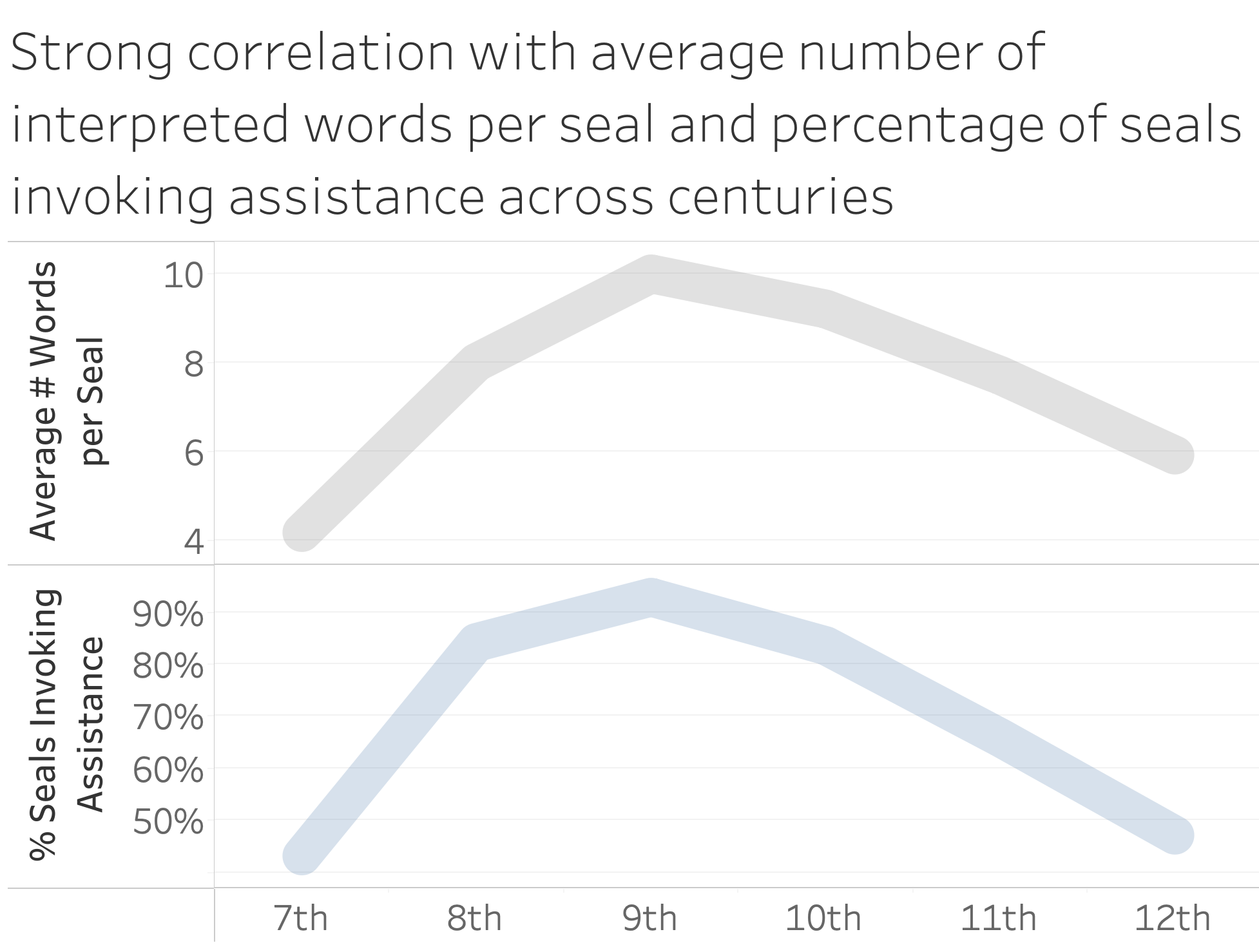

Seals in the 9th century, where assistance was most invoked, also tended to have the most inscribed words

Strongly correlated with the conformity of 9th century seals to invoke divine assistance () is the number of interpreted words in the Inscribed Text Field. I use the word “interpreted” to indicate that many of seals contain abbreviations (or illegible/missing text) that are expanded into full words in the online catalog. As an example, for this particular seal, the obverse bears the inscription “Κε βθ τῷ” and the reverse the inscription “Ῥω..ν σπαθ β νοταρ τῆς σακέ.λ,.” The Online Catalogue interprets this inscription to be “Κύριε βοήθει τῷ σῷ δούλῳ Ῥωμανῷ πρωτοσπαθαρίῳ καὶ βασιλικῷ νοταρίῳ τῆς σακέλλης” (Lord, help your servant Romanos, protospatharios and imperial notarios of the sakelle). In this example, nine inscribed “words/abbreviations” were expanded into 12 individual words by the cataloguers.

If (and I realize this is a big if) the seals are relatively uniform both in condition and how they use abbreviations across the centuries, seals of the 9th century show a marked verbosity. On average, they contain around 10 interpreted words per seal versus about 4 words for the 7th century and 6 words for the 12th century. See .

Figure . Average number of interpreted words per seal (top) versus percentage of seals invoking assistance (bottom). For word count, interpreted words in Greek/Latin counted, not English translation. (Correlation, R2 = 0.90, p < 0.05)

Seals for centuries with most invocations show the least variety in words choice

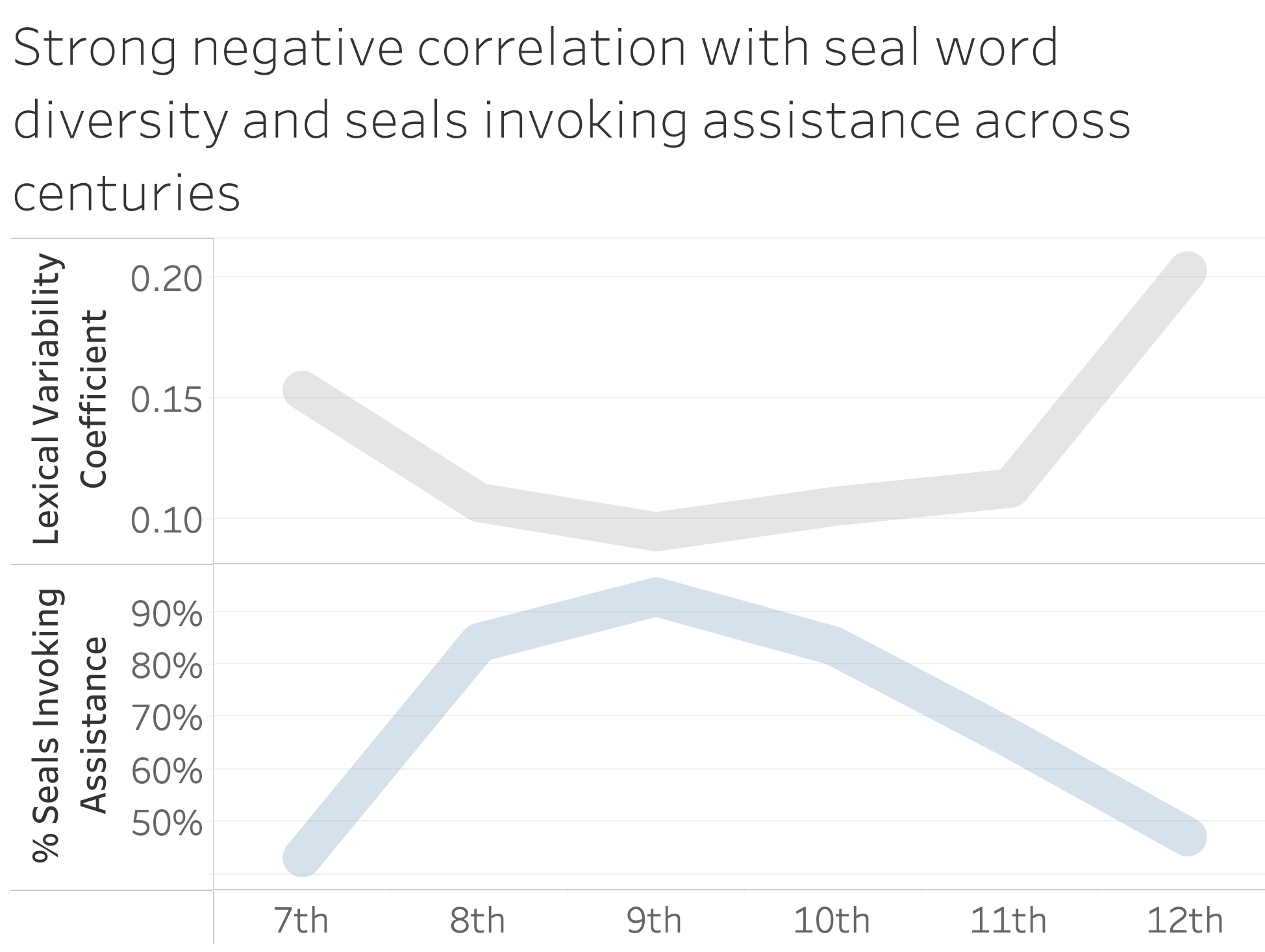

While the seals of the 9th century are more verbose than those of other centuries, the actual wordings they use are much more conventionally formulaic. To test for this, I developed a measure called the Lexical Variability Coefficient. For each century, I count the number of unique words used (e.g., “mother” would be counted as one unique word) and divided this by the total number of words used overall in the Interpreted Text Field (e.g., “mother” would be counted every time the word is used across all seals for the century).[17] See .

Figure . Lexical Variability Coefficient (Number of Unique Words / Total Number of Words) (top) versus percentage of seals invoking assistance (bottom). In the 9th century, for every 10 additional words inscribed on seals, less than 1 new word was introduced overall. In the 12th century, this was more than double. (Correlation, R2 = 0.74, p < 0.05)

Notably, while the seals of the 8th-10th centuries use the most words (, top), they say the fewest different things (, top)!

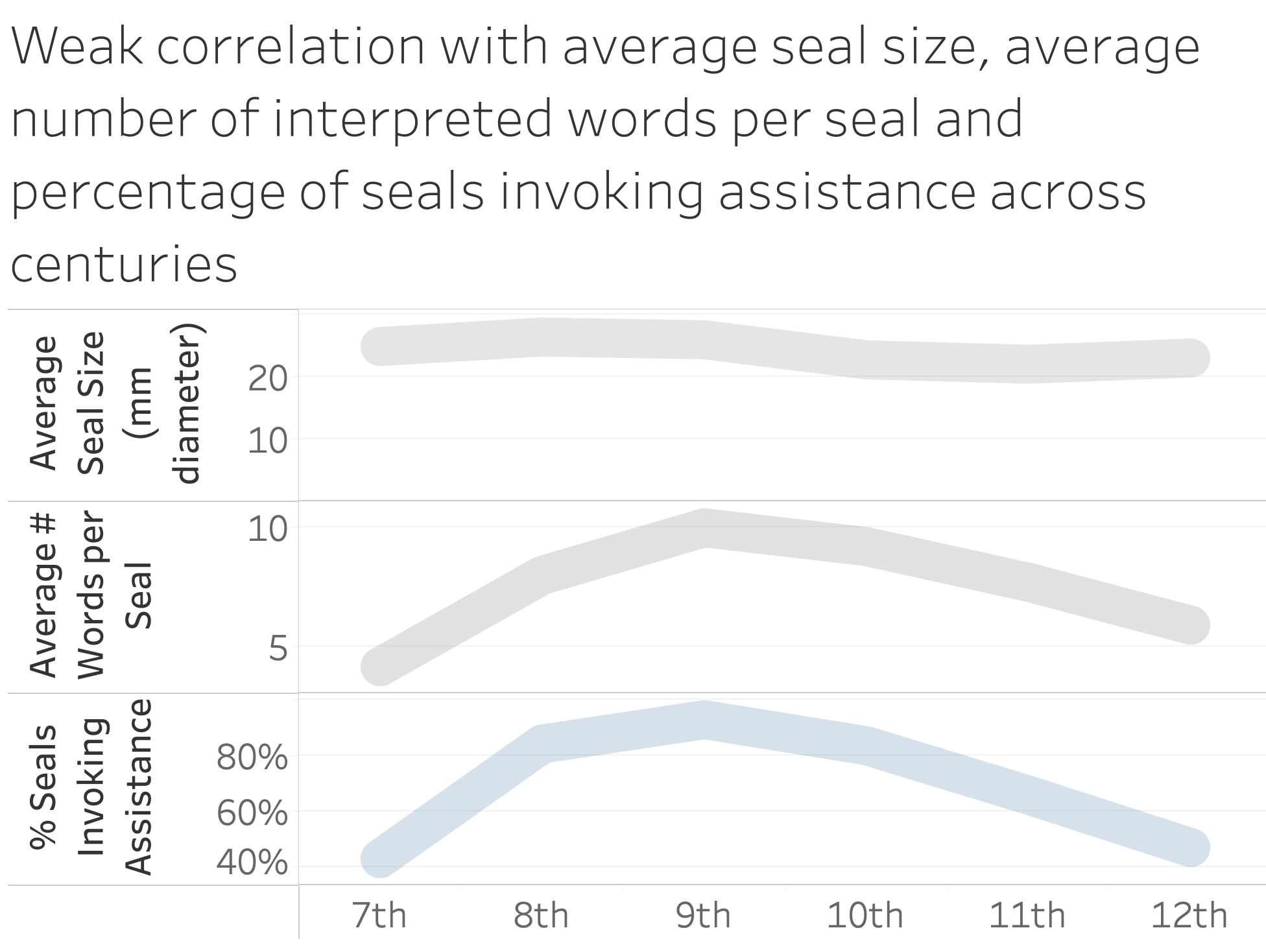

Seal size (diameter) not correlated with the number of words inscribed

So far in this analysis, we have mostly examined the Catalogue’s description of the text inscribed on our seals. Inspired by the strong correlation between average number of words used per seal and the percentage of seals invoking assistance (), it seems reasonable to ask if there might be other attributes listed in the Catalogue that, in turn, might directly impact the number interpreted words inscribed.

One obvious attribute to examine in this regard is seal size. Arguably, the larger a seal is, the more words that can be inscribed onto it. Indeed, seals of the 9th century tend to be larger in diameter on average (26 mm) than those of the 7th (25 mm) and the 12th (23 mm) and have more words (). However, 8th century seals, for example, aree on average the largest (26.5 mm) across the centuries but tend to have fewer interpreted words than those of the 9th century. In general, for the seals examined, seal size has little correlation with seal verbosity (and consequently, little correlation with whether seals invoked divine assistance). See .

Figure . Average Seal Size, Seal Verbosity and Proportion invoking divine aid across centuries. (Weak correlation between average seal diameter and % seals invoking assistance across centuries, R2 = 0.05, p > 0.5)

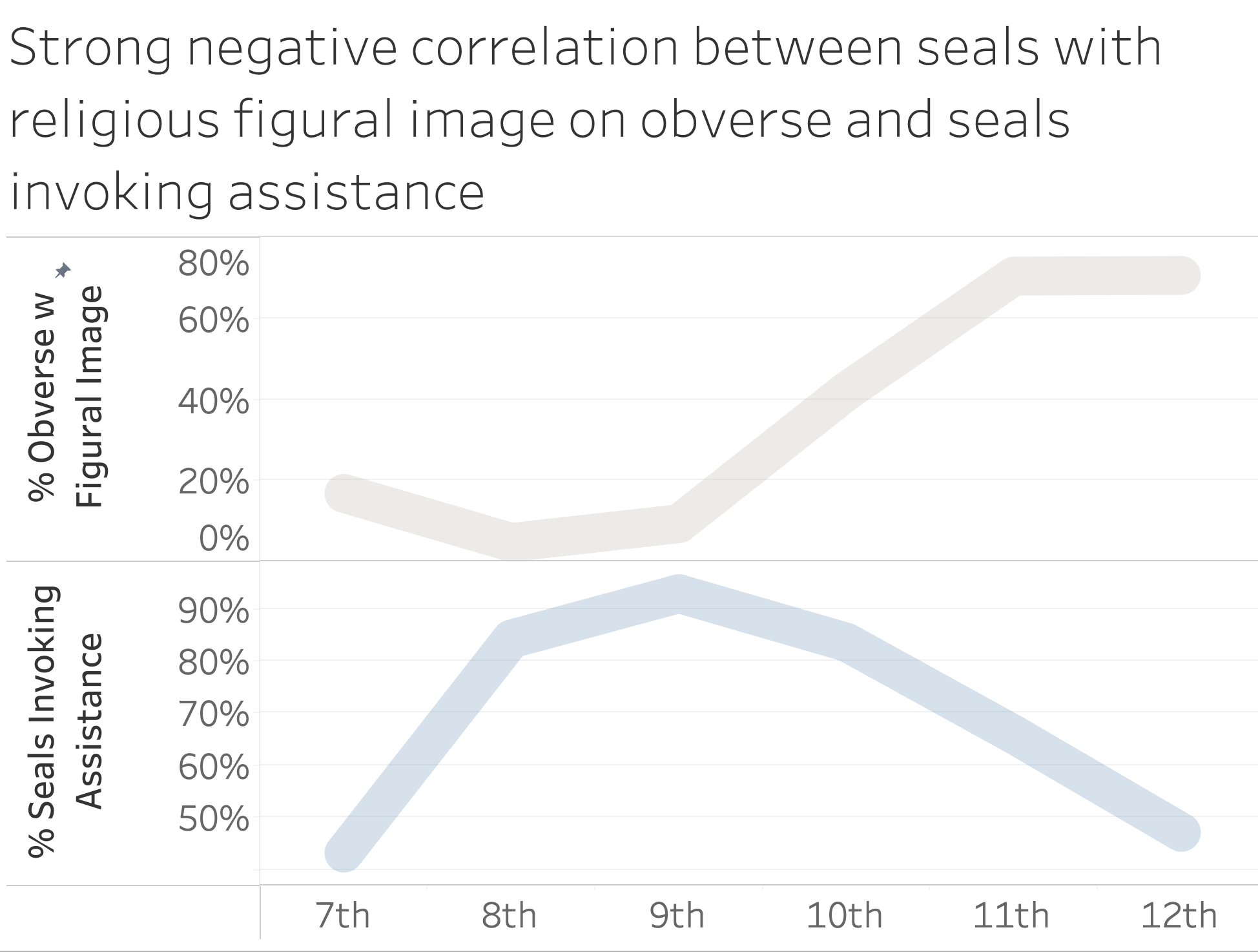

Practice of showing religious figural image on obverse only moderately correlated with whether divine assistance is invoked

If the seal size has little correlation with the number of words inscribed, perhaps there are other features that might? For example, it might be argued that the practice of showing a figural image on a seal gave its owner less of a field for words and less of an opportunity to invoke divine assistance. [18]

Figure . Percentage of seals by century where the obverse portrayed a figural religious image (top) versus percentage of seals invoking assistance (bottom) (Correlation R2 = 0.79, p < 0.05)

All else being equal, there is strong support for the idea that showing figures on a seal’s obverse negatively correlated with inscribed invocations for assistance. From a practical standpoint, there would less room for inscribed text. Of course, it might also be argued that portraying a religious figure on a seal might be considered as an implicit invocation for assistance (making a textual invocation less important). See .

Devoting space on the seal’s reverse to inscribed text doesn’t generally lead to more invocations

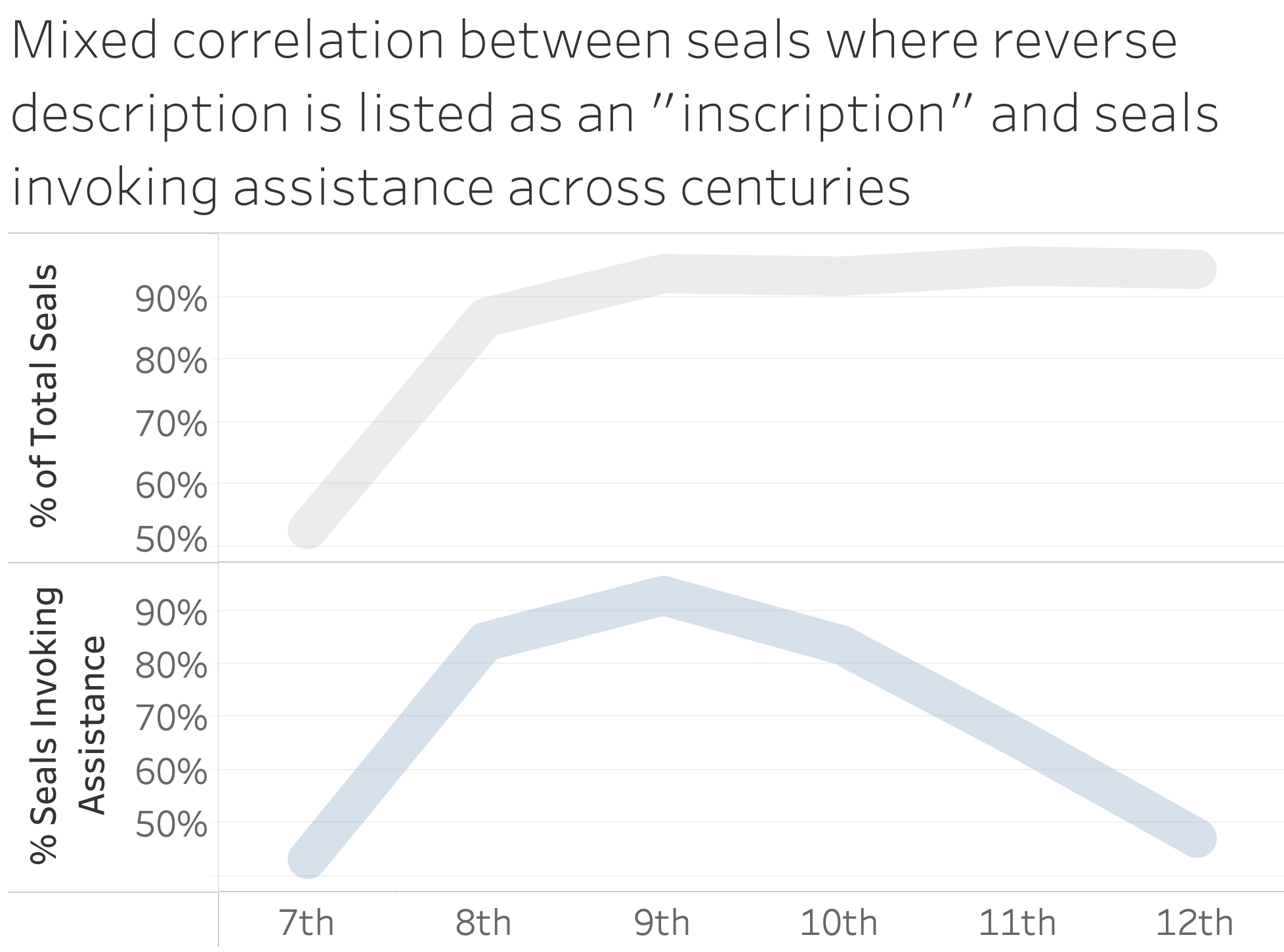

In considering possible seal attributes that might correlate with the practice of inscribed invocations, we have looked at both the overall size of the seal and whether the obverse of the seal had a religious figural image. The next and last seal attribute examined for this paper is the seal reverse. For the majority of the seals studied (about 90%), the Catalogue Reverse Description Field suggests the reverse is mostly text. However, across the centuries, this practice only shows mixed correlation with the practice of inscriptions expressly invoking divine assistance. See .

Figure . Percentage of seals where reverse is listed as mostly being an inscription (top) versus percentage of seals invoking assistance (bottom) (Correlation R2 = 0.64, p > 0.05)

From the 7th century to the 9th century, the proportion of seals containing mostly an inscription on the reverse and the proportion of seals explicitly invoking assistance seem to track quite nicely. However, this is not the case looking from the 9th century to the 12th century. It is not that seals of these centuries had less of an easy opportunity to invoke assistance in their text, it seems a deliberate choice.

Discussion

The central finding of this paper is that seals in the 9th century are much more likely to expressly invoke divine assistance in their inscriptions. What could explain this trend?

Could it be that people in the 9th century were much more pious than those, say, in the 7th or 12th century?

As silly as this proposition might sound to a Byzantinist, it is a question that should not be dismissed out of hand. If anything, recent research into Byzantine culture and society has highlighted the fact that it is far more nuanced and heterogenous than had been postulated in the past.[19]

A scholarly examination of this question cannot rely on sphragistic evidence alone. Some other points of information that might help inform this question would be to look at some other indicators of relative piety such as distant readings of other types of text (correspondence, grave markers, laws, legal decisions, etc.) and trends in the establishment of new churches or monasteries.

Could it be that there were historically unique factors in the 9th century that led to the relatively uniform practice of expressly invoking divine assistance on seals?

Certainly, the 8th and 9th centuries are notably marked by a religious polarization around icons. On one hand, the iconoclasm debate revolved around the idea of how to properly worship the divine (not on the question of piety itself). From this perspective, iconoclasm in itself might not have had much direct impact on the practice of inscribed invocations. On the other hand, perhaps this theological polarization might have encouraged the owners of seals to search for a commonality to be expressed in the seals they commissioned and sent. Perhaps the turbulence of the time uniquely encouraged people to expressly invoke divine assistance?

Could it just be a change in cultural conventions (i.e., fashion) in what senders inscribed on their seals?

While I argue that attributes on seals offer a personal expression of the individual, they are also a product of cultural conventions (much like modern day business cards). Perhaps, rather than indicating different levels of personal piety across centuries, the practice of inscribed invocations for assistance that peaked in the 9th century merely marks changes in fashion[20] or just some sort of random drift[21] in cultural conventions?

Could this just be an artifact of the cataloguing process?

Finally, there is a possibility that an explicit invocation for divine assistance might, in itself, guide the cataloguer to ascribe an 8th-10th century epoch to the seal. Dating a seal is an inherently subjective hermeneutic process.

Conclusion

The value of any historical analysis is not so much its ability to reach definitive answers, but in its ability to help inspire new and better questions. The central phenomenon this analysis presents is the relatively striking conformity among seals from the 8th – 10th century to invoke divine assistance. The new (and, hopefully, “better”) question to explore is “Why?”

Methodology

To “scrape” (iterate through the various pages and capture information about items) the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Seals Online Catalogue, I used a tool called Octoparse. First, I programmed Octoparse to iterate through each page of the Catalogue (with no filters selected), select each seal listed to get an item view page and then pull information listed about each seal into selected fields. While this gave base information about each seal, it did not give information about how the seal had been tagged by Century, Location, Title, Office, or Language. To get this information, I then programmed Octoparse to iterate through each of the filter types (Century, Location, Title, Office, Language) and capture this accession numbers of seals that matched these filters. This led to six individual data files.

To clean the information, I used a tool called Tableau Prep which allowed me to join the six data files for each seal to each other to create a master file with records for each seal that contained both information contained in the item view page and the filters.

To analyze and visualize the data, I mostly used a tool called Tableau Desktop. In addition, in order to develop the Lexical Variability Coefficient, I used two Browserling.com tools here and here.

It is my plan to create a public GitHub repository to archive both the raw information captured and cleaning process for future scholars to both examine my analysis and build on it.

Bibliography

Bentley, R. Alexander, Matthew W. Hahn, and Stephen J. Shennan. “Random Drift and Culture Change.” Proceedings: Biological Sciences 271, no. 1547 (2004): 1443–50.

Cotsonis, John A. The Religious Figural Imagery of Byzantine Lead Seals I: Studies on the Image of Christ, the Virgin and Narrative Scenes. London: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429327193.

———. The Religious Figural Imagery of Byzantine Lead Seals II: Studies on Images of the Saints and on Personal Piety. London: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429327216.

Drpić, Ivan. “The Patron’s ‘I’: Art, Selfhood, and the Later Byzantine Dedicatory Epigram.” In Epigram, Art, and Devotion in Later Byzantium, 89:895–935. Cambridge University Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43577194.

Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 005, no. 1 (March 10, 2011).

Kazhdan, A. P., and Ann Wharton Epstein. Change in Byzantine Culture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. University of California Press, 1990.

Moretti, Franco. “Conjectures on World Literature.” New Left Review, no. 1 (February 1, 2000): 54–68.

Oikonomides, Nicolas. “The Usual Lead Seal.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 37 (1983): 147–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291481.

“Politics and Government in Byzantium: The Rise and Fall of the Bureaucrats (New Directions in Byzantine Studies): Shea, Jonathan, Stathakopoulos, Dionysios.” Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.amazon.com/Politics-Government-Byzantium-Bureaucrats-Directions/dp/0755601939.

Seibt, Werner. “The Use of Monograms on Byzantine Seals in the Early Middle-Ages (6th to 9th Centuries).” Parekbolai. An Electronic Journal for Byzantine Literature 6, no. 0 (June 19, 2016): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.26262/par.v6i0.5082.

Footnotes

-

Many thanks to Jonathan Shea of Dumbarton Oaks for his help and guidance in answering questions about the Catalogue itself and how to interpret the information it contains. All errors made in the analysis are solely the responsibility of the author. The Dumbarton Oaks Online Catalogue of Byzantine Seals can be viewed and searched here. ↑

-

On 11/8/21, when the data was scraped from the Online Catalogue, the catalogue contained 15,100 seals of the approximately 17,000 seals in Dumbarton Oaks entire collection. Additions to the Online Catalogue are made on almost a daily basis. In selecting the set of 13,600 seals examined from the available 15,100 records available online on this date, seals falling outside the 7th – 12th centuries, not coded as being in Greek or Latin and not having a searchable Inscribed Text Field entry were excluded. ↑

-

Cotsonis, The Religious Figural Imagery of Byzantine Lead Seals II, 4. ↑

-

Seibt, “The Use of Monograms on Byzantine Seals in the Early Middle-Ages (6th to 9th Centuries),” 2. ↑

-

For an overview of the role and importance of seals, see Oikonomides, “The Usual Lead Seal.” ↑

-

“Politics and Government in Byzantium: The Rise and Fall of the Bureaucrats (New Directions in Byzantine Studies): Shea, Jonathan, Stathakopoulos, Dionysios,” 10. ↑

-

For a fascinating discussion of the emotive and performative functions of Byzantine epigrams that directly considers how written text was used to reflect a Byzantine performative-self see Drpić, “The Patron’s ‘I.’” (especially p. 98). ↑

-

Particularly impressive is the work of John Cotsonis who was doing “Digital Humanities” before Digital Humanities was “cool.” For a compilation of many of his articles quantitatively examining Byzantine seals, see Cotsonis, The Religious Figural Imagery of Byzantine Lead Seals I; Cotsonis, The Religious Figural Imagery of Byzantine Lead Seals II. ↑

-

Moretti, “Conjectures on World Literature.” ↑

-

Drucker, “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.” ↑

-

For a discussion on the Dumbarton Oaks cataloging process see here. ↑

-

Unfortunately, I find that many people in the humanities are more likely to dismiss a quantitative finding that wrestles with shades of gray than they will dismiss a qualitative finding built on similarly nuanced information. ↑

-

Key words searched for in the Inscribed Text Field to code for an invocation were “help,” “aid,” “protect,” “watch over” or “save.” While in some instances, these invocations might be made a non-divine being, such as an emperor, the instances are so few as not be statistically significant. ↑

-

Key words used in the Inscribed Text Field to assign Christ include “Christ,” “Jesus,” “Savior” and “Lord” (there are a small set of seals where the term “lord” is used, but do not denote Christ). Key words used to assign the Virgin include “Mother of God,” “Virgin,” “Lady” and “Mother of the Divine Word.” The programmatic logic used for the analysis favors “Christ” over “Virgin.” For example, if the Inscribed Text Field contained the words “Mother of God and Lord” the logic would assign “Christ” over the “Virgin” regardless of the fact the Virgin was mentioned first. This logic should not skew general findings, only 375 seals (about 2% of the total number of seals) have Inscribed Text Fields that contain keywords for both “Christ” and the “Virgin. ↑

-

For a discussion regarding the depiction of saints on seals as a reflection of general cultural trends, see Cotsonis, The Religious Figural Imagery of Byzantine Lead Seals I, 73. ↑

-

and use slightly different approaches for counting total words in the Greek/Latin interpreted text that give slightly different results. My working hypothesis is that one of the methods used for calculating words would consider “. . .” (with the spaces between periods) as three individual words while the other approach would count it as one. While the differences between algorithms might slightly alter my findings, I consider the impact to be relatively inconsequential. Nevertheless, this phenomenon requires additional investigation in the future. ↑

-

The Obverse Description Field offers unique challenges to a “distant reading” exercise. Because descriptions could be quite complicated in this field (e.g., Mother of God holding the Christ Child with a cross above), this analysis seeks to capture the most prominent element of the Obverse Description Field by programmatically considering the relative position of key search words. In the example above, the Obverse would be considered as primarily featuring the Virgin rather than Christ or a Cross because “Mother of God” is mentioned before other key words in the field text. Seals considered to portray a religious figural image are those that portray Christ (which was relatively rare), the Virgin (very common) or a Saint (fairly common). ↑

-

See, for example, Kazhdan and Epstein, Change in Byzantine Culture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. ↑

-

For a discussion of changing fashions used in Byzantine seal invocative monograms, see Seibt, “The Use of Monograms on Byzantine Seals in the Early Middle-Ages (6th to 9th Centuries),” 8–10. ↑

-

Bentley, Hahn, and Shennan, “Random Drift and Culture Change.” ↑