Paul Albert

11/2/20

From Artisan to Artist:

The Journey of a Social Construction

What is an “artist?”

Like all questions of word definition, the answer is always contingent on when/where/whom you ask. Words like “artist” are cultural constructs, always shifting toward various gravitational equilibriums through an interplay of opposing and conjoining forces. Today, when thinking of an artist, we often picture such ideas as the social outsider, the suffering genius and the person born with unnatural talent.

If you posed the question “what is an artist?” to Giorgio Vasari he would not have had a ready answer. The concept “artist” as we know it had not been proposed, contested or redefined. Yet, we commonly call Vasari’s book published in 1550 “The Lives of the Artists.” In fact, Vasari’s book was actually titled Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori (Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects).

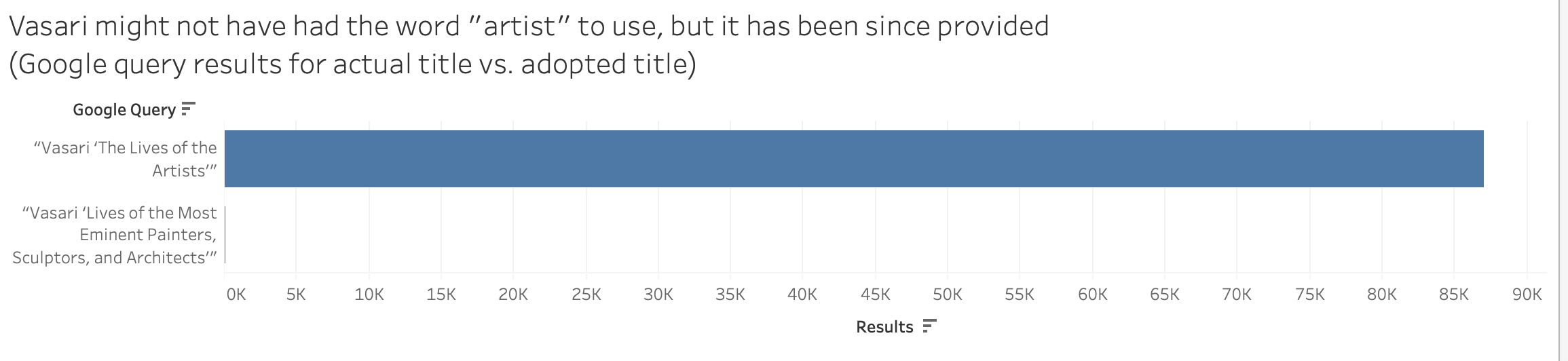

The hegemony of the term “artist” to characterize the painters and sculptors spoken about in Vasari’s book can be evidenced in comparing two Google queries. A search for “Vasari ‘The Lives of the Artists’” finds over 80,000 results. In contrast, a search for the actual title “Vasari ‘Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects’” returns less than 100 results.

Figure 1. The reformulation of the title of Vasari’s book indicates a clear shift in thinking about its biographical subjects.

I argue that the relative popularity of the title “Lives of the Artists” versus its actual title “Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptor and Architects” reflects not a matter of convenient brevity, but instead a categorical cultural shift in thinking about Vasari’s painters and sculptors from his time to today. In this journey, certain objects and methods of production were separated from other types of objects and methods of production to become “Art” (e.g., painting, sculpture, literature, music, poetry, acting, architecture?, photography?, fashion?), certain practitioners became defined as “Artists” and certain institutions and market structures were fashioned and transformed in ways that both mediated and were mediated by these journeys.

The goal of this paper is to explore this cultural change as it occurred in Western culture (in about 5,000 words).

16th Century Florence, Our Journey Begins

We begin our journey in 16th century Florence realizing that this time/place is just a useful waypoint to examine, but definitely not a definitive origin for the idea of the “artist.”

In writing the Lives of the Artists in 1550, Vasari built on an intellectual heritage that included classical writings (Plato, Aristotle and especially Plutarch’s Lives[1]), medieval hagiography on lives on various saints[2] and the attending rhetorical conventions and tropes that provided models on how to create a compelling read.[3] Michelangelo, the book’s penultimate hero, is stated to have been actually “divine” and, like any self-respecting saint, the book describes recounts how Michelangelo’s corpse did not show any decay after 25 days in the coffin.[4]

But despite affirming the transcendental nature of his subjects, Vasari had not the term “artist” to use to describe them. Indeed, neither did the classical Greeks or Romans before him[5]. Nor did any other European language of his time. [6] Instead, the term Vasari most often used refer to his biographical subjects was artificer. This was a word that did not just designate painters and sculptors. The word artificer was used for men and women that deployed talent and rule to fashion their work and could have included shoemakers, opticians, hat makers, cameo makers, carriage makers and hundreds of other types of people making products.

Like most other artificers, painters and sculptors were regulated and supported by guilds. Painters, reflecting their need to source and prepare pigments, most often belonged to a druggist/medical/spice guild. Sculptors most often belonged to a goldsmithing or stone mason guild.[7] In contrast to our idea today of the independent artist seeking freedom of expression, the painter in Vasari’s time was more a due paying member of an early version of a trade union. Also, like many other artificers, the proto-artists in Vasari’s book did not create for the sake of creation, they created to satisfy specified demands. Vasari’s painters worked almost exclusively under a patronage system.

A fifteenth-century painting is the deposit of a social relationship. On one side there was a painter who made the picture, or at least supervised its making. On the other side there was somebody else who asked him to make it, reckoned on using it in some way or other. Both parties worked within institutions and conventions—commercial, religious, perceptual, in the widest sense social—that were different from ours and influenced the forms of what they together made.

- Michael Baxandall [8]

Under a patronage system, a patron (e.g., rich merchant, church official, public institution) would contract with a painter or sculptor to produce a specific work and provide contractual terms often specifying materials, size and intended destination for that work. For example, the painter was not just asked to produce just an altarpiece, they were asked to produce an altarpiece of a certain dimension using certain materials (e.g, a specific quality of lapis lazuli blue) with a certain pictorial theme to be placed in a certain location in a certain church. In many senses, the work produced by the painter signified as much about the patron as it did about the artist. ,[9]

One of the most forceful myths of the Renaissance is the idea that its artists freely explored their ideas and created their masterpieces for enlightened patrons eager to acquire these works of genius’. Rather, ‘it was the patron who was the real initiator of the architecture, sculpture, and painting of the period’[10]

Also, much different from today, the painter of Vasari’s time worked not to produce a “singular item” to be put in isolation on a wall, they instead worked to produce an “integrative component” that complimented and enhanced its surroundings. As such, the product of the artist was not just judged in itself, but also by its utility in enriching its environment (and signaling status for its patron). Indeed, if recompense can be judged a measure of relative esteem, it is worth noting that the workers who created the frames for paintings in the renaissance were often esteemed and paid as much or more than the painters who created the paintings.

Not only did the internal logic of patronage shape the nature of the painter’s output, it also shaped the social/commercial persona of the painter. In being contracted to create a specified product that had a specific utility, the painter was not too categorically different from the blacksmith asked to cobble a shoe for a specific horse.

For sure, however, there was a reason that Vasari did not write a book called “The Lives of the Most Eminent Blacksmiths, Cobblers and Carpenters.” While Vasari and contemporaries saw painters and sculptors and their work as being more elevated than that of the blacksmith, these painters and sculptors still operated within a patronage system that, for the most part, did not. It is in this perspective that we can partially understand that, according to Michelangelo’s contemporary biographer Condivi in 1553, Michelangelo’s family saw his choice to become an artist as shameful and bringing dishonor.[11]

Still, to Vasari and many others to his time, there was something special about painters and their work. Certainly, the use of painting and sculpture up to this time to create spiritual/civic belonging and to signal status meant, by essence, that there was something significant about paintings and sculptures. It did not take much of a leap to suggest there could also be something special about the people who made these works. Vasari certainly does this. But for the purpose of our journey, Vasari never, nor was conceptually equipped to, suggest that painters and sculptors shared a categorical professional essence that allowed for them to be set apart from other professions.

While Vasari evangelized the idea that great painters and sculptors were graced by God with genius and talent, what is generally absent in both Vasari’s writings and thinking up to this period was the idea of the artist as being marked by imagination, originality and autonomy.[12] Like other craftspeople, the painters craft depended on learning technique and established methods (e.g., perspective) and applying their efforts according to rules. In this sense painters were thought of more like scientists than our modern image of the artist as a free-spirit creating new expressions and gateways to the sublime.

Through classical times to Vasari, judgement of a painting did not rest solely on beauty, but for a large part on well how the painters applied their skill within the rules of their craft[13] and fit the use it was intended for. In comparing medieval thoughts on art to today’s, Larry Shiner notes:

If an artificer, Aquinas said, should decide to make a saw more beautiful by constructing it out of glass, the result would not only be useless as a saw and thus a failed piece of art, it would not be beautiful either (Summa Theologica I—II, 57, 3c). Today, of course, making a saw out of glass would guarantee it to be a work of art, perhaps exhibited under the title ‘Aquinas’s Saw.’[14]

When considering the visual merit of a painting, Vasari and his contemporaries did not single out creativity and expression as we do today. They asked how well the painting was able to faithfully reproduce (copy) nature. Indeed, Vasari argued that painting had reached an ultimate perfection in Florence through, above all, accurately showing perspective and faithfully rendering nature.[15]

Conformity to rules of production and technique not only defined how Vasari’s painters and sculptors were able to fashion their work, conformity to rules of society and etiquette were demanded of Vasari’s painters in order to obtain work. Often overlooked through our the romantic lens with which we view the renaissance artist, the logic of the patronage system demanded that successful painter be very much a cultural insider versus the modern trope of the artist as social misfit. As one example, in Giovanni Battista Armenini’s 1587 treatise, Of the true precepts of painting (De’ veri precetti della pittvra), the bulk Armenini’s guidance is not spent discussing techniques of painting, but the techniques of business, how to attract patrons through proper decorum and etiquette. [16]

Toward Today, Our Journey Progresses

In order to characterize the journey of the idea of “Artist,” we started by looking at Vasari and his times. We found a world that did not have such a category, but yet had an appreciation for paintings and the people who made them. Rather than social outcasts tapping into the spirit of the sublime to produce objects demanding contemplation[17], we found instead courtiers applying skillful technique driven by rules to produce works demanded in order to provide utilitarian purposes.

When speaking of cultural construct such as the term “Artist,” it is important to note that this is an idea that emerges over time and in pieces at a different pace in different places. Often, it is hard to discern a clear start and there never is a true end as categories such as these are always contested and redefined. Yet, today, we can safely say that there does indeed exist at least an actively contested idea of the “Artist.” Most would agree that it includes painters, sculptors and musicians. Of Vasari’s triumvirate, painting, sculpture and architecture, architecture seems most out of place for being considered an art today. Perhaps because it seen as adhering too much to rules and engineering principles?

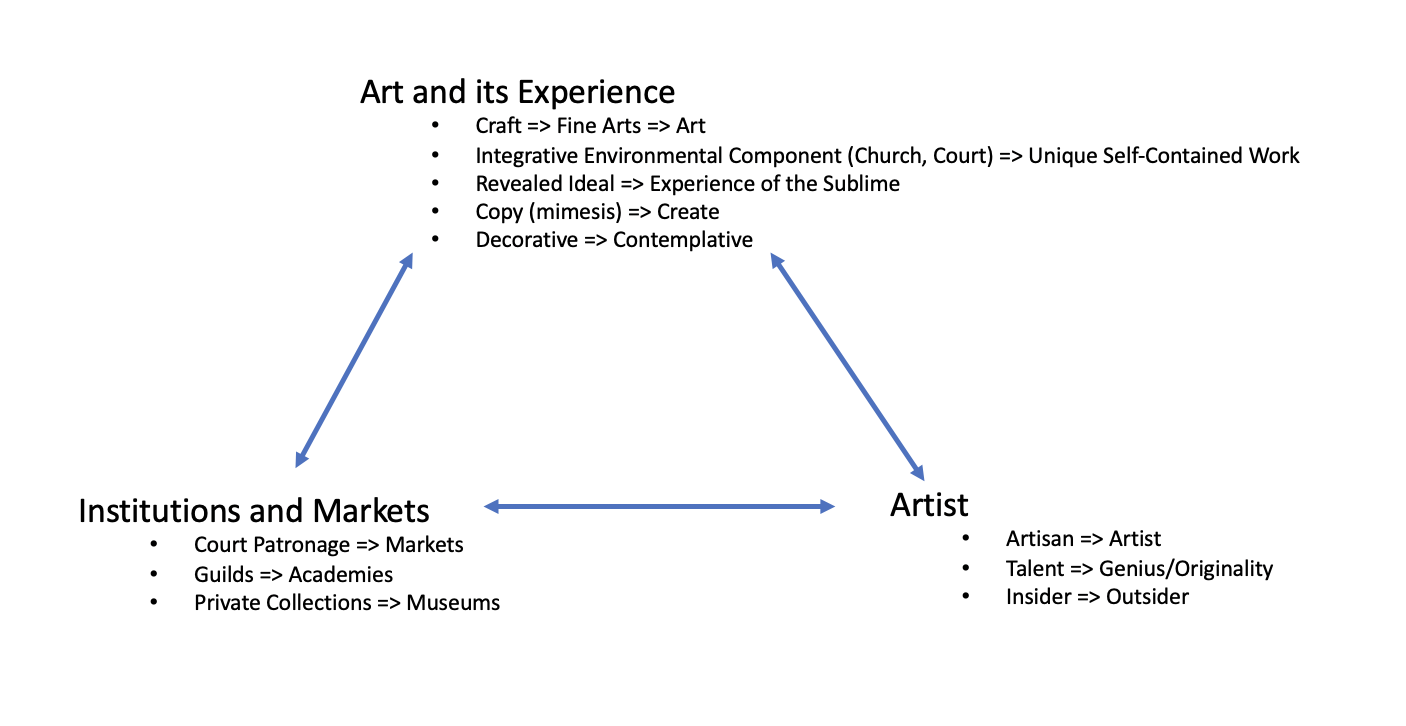

Rather than one thing changing from Vasari’s time to today, it was the interplay of institutions, markets, cultures and people that has given the Western world our modern idea of the “Artist.”

Figure 2. The interplay of factors leading to the concept of the “Artist”

Many point to the rise of an affluent art loving middle class and the consequent flourishing of an art market as an important development for the artist in Western history. This cannot be disputed. However, moving from a system largely based on patronage to a system largely based on markets did not, in itself, propel the distinction between artist and artisan.[18]

Indeed, many other professions moved from being part of a patronage system as well without being elevated the way the idea of an artist has been elevated. It can be argued, perhaps, that while not propelling this distinction in itself, the move to markets gave artist a freer hand in their efforts to distinguish themselves from artisans.

Likewise, many also point to the reformation and counter-reformation as significant developments for artists in Western history. Again, this cannot be disputed. Without a doubt, the reformation and counter-reformation decisively affected demand for the painter’s work. In places where the reformation took root, artists saw an important source of demand, the church, virtually disappear. In places where the counter-reformation took root, artists conversely saw a greater demand for their work. In some cases, artists they were tasked with refilling churches where centuries of art that had been sacked by reformational zeal. In all cases, the counter-reformation placed a renewed emphasis of the utility of art to spiritually consecrate the space of the church.

These changes in demand did little in themselves to directly fuel the distinction between artists and artisan. However, the reformation did lead to an important institutional practice which had a significant impact on driving this distinction, the creation of the museum. Nicholas Wolterstorff observes that the iconoclastic fervor of the reformation which led the churches to be to be stripped of images led to a demand to reformulate these images into works of art in a museum:

Museum culture, which arose in northern Europe in response to more than a century of religious violence, represents a solution to that violence. Exhausted by religious violence and, exhausted in particular, by the attempt to break images, eighteenth-century northern Europeans invented a new solution for religious artifacts, and especially for religious paintings and sculptures. They stopped smashing them, and instead acknowledged that religious artifacts could be beautiful; they placed those artifacts under the aegis of a new discourse, invented for the purpose, that of aesthetics… . The museum reinvented the category of the adiaphora, “things indifferent,” things that do not save or damn—things, etymologically, that do not bear weight. The museum permitted the space for artifacts from mutually hostile traditions to be grouped in the same space[19]

The resignification of paintings and sculptors that museums imposed on these works was accompanied by a change in how these objects were thought of. Wolterstorff further notes,

Whereas devotion was required of those who engaged images in the church, it was taste that was required of those who engaged images in the museum. The central eighteenth-century tradition of taste … decisively protected the religious image, by recategorizing its function as art. No longer was religious painting numinous and salvific; it was now framed, buyable, socially specific, and a fit ground for the cultivation of the gentleman’s taste. No longer, indeed, was the religious image an image, let alone an idol, but it was art. The space of the image shifted from the hot church to the private, though semi-public space of the cool museum. [20]

It was not just the reformation that led to the growth of museums. Works of art that were moved from churches to museums soon found company from other sources. In the eighteenth century, popular movements brought works from palaces to museums as well in France, England and Germany. Paintings and sculptures that were not destroyed by mobs driven by religious or political indignation were repurposed from their original intent to signal spiritual or political distinction and reframed as objects possessing a common essence of beauty worthy of exploration as works “in and of themselves.”

It was at this moment in history, when artistic objects were removed from their original context and displayed together in a new context that the idea of the aesthetic was begun. The idea of beauty, defined through antiquity not only in terms of pleasure, but also in terms of expression of moral value and utility[21] shifted with the enlightenment to also propose that there was more than pleasure, utility or taste involved in appreciating art. Immanuel Kant, for example, in his aesthetic proposed that a proper appreciation of art needed to be disinterested, not ask like a Renaissance patron would if a work fulfilled its stated purpose, but instead if the works intrinsically would give pleasure or a sense of the “sublime.”[22]

The creation of the museum to elevate objects into art and new ideas of aesthetics changed the discourse about art. From classical times through most of the seventeenth century the term art was used to describe a way of fashioning and was often broken down into liberal arts (poetry, grammer, rhetoric, music, geometry, etc.) and mechanical arts (cloth making, metal work, agriculture, painting and sculpture).[23] By the end of the next century, however, painting and sculpture began to be categorized more closely to the liberal arts. Beginning in the mid-1700’s, painting, sculpture, painting and music began to be seen as categorically similar and were variously called the “elegant arts,” “noble arts” or “higher arts.” However, it was the French term “beaux-arts”, first used in 1746[24], that won out and was directly translated in German (“schoenen kiinste”), Spanish (“bellas artes”) and Italian (“belli-arti”). In English, this idea was translated into “polite arts” and, more frequently as “fine arts.”[25]

As the concept of “Art” began to take hold, new ways of thinking about art appeared. A major conceptual shift occurred in 1764 when J.J. Winkelman wrote a book, not about the lives of individual artists, but about the evolution of art itself.[26] This book, History of Ancient Art, was the very first book every published with the term “history of art” in its title.[27] Roughly around this time, the idea of the artist began to more closely resemble our own. In 1762, the Académie Française created this dictionary definition of an “artist” – “he who works in an art where genius and hand must concur.”[28]

As the creation of the museum and the propagandization of the aesthetic worked to enshrine the idea of Art and, by extension, the Artist, artists and industrialization were working to further widen the conceptual gulf between artist and artisan. Painters and sculptors created academies to replace the guilds they had belonged to distinguish their professions. Vasari, himself, was influential in helping to establish such an academy for painters, sculptors and architects in Florence in 1563[29] A similar academy (Accademia di San Luca) was founded in Rome in 1577.[30] In France, a royal mandate created the the Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1648[31]. Soon most European cities had similar institutions. Unlike the guilds lumping artists in with other craftspeople, these academies provided an institutional heft to the artists’ contentions that they were no mere craftspeople.

The gulf between artist and artisan became even greater for as artists were able to rise in esteem, other craftspeople faced existential threats to their profession. Increased mechanization and a fragmentation of labor directly challenged guild structures that emphasized continuity and learning of a craft. It was no longer a cobbler making shoes or a glass artisan making a bottle. It was rather a combination of machinery and people linking separate steps of manufacture.

Evidence of A Growing Cultural Focus on the Artist

Very generally speaking, one can say that the urge to name the creator of a work of art indicates that the work of art no longer serves exclusively a religious, ritual, or, in a wide sense, magic function, that it no longer serves a single purpose, but that its valuation has at least to some extent become independent of such connections. In other words, the perception of art as art, as an independent area of creative achievement—a perception caricatured in the extreme as “art for art’s sake”—declares itself in the articulation of the growing wish to attach the name of a master to his work. [32]

Like most cultural constructs, the idea of the Artist did not happen suddenly or even concurrently across geographies. Yet, looking for evidence of the shifting importance of the artist’s hand helps us understand at least the direction of this shift. As one example, exhibition catalogs in France and England which had usually listed artwork according to wall placement and often neglected to mention the name of the painter increasingly began listing the artist name first or even indexing listings by artists by the mid-eighteenth century.[33]

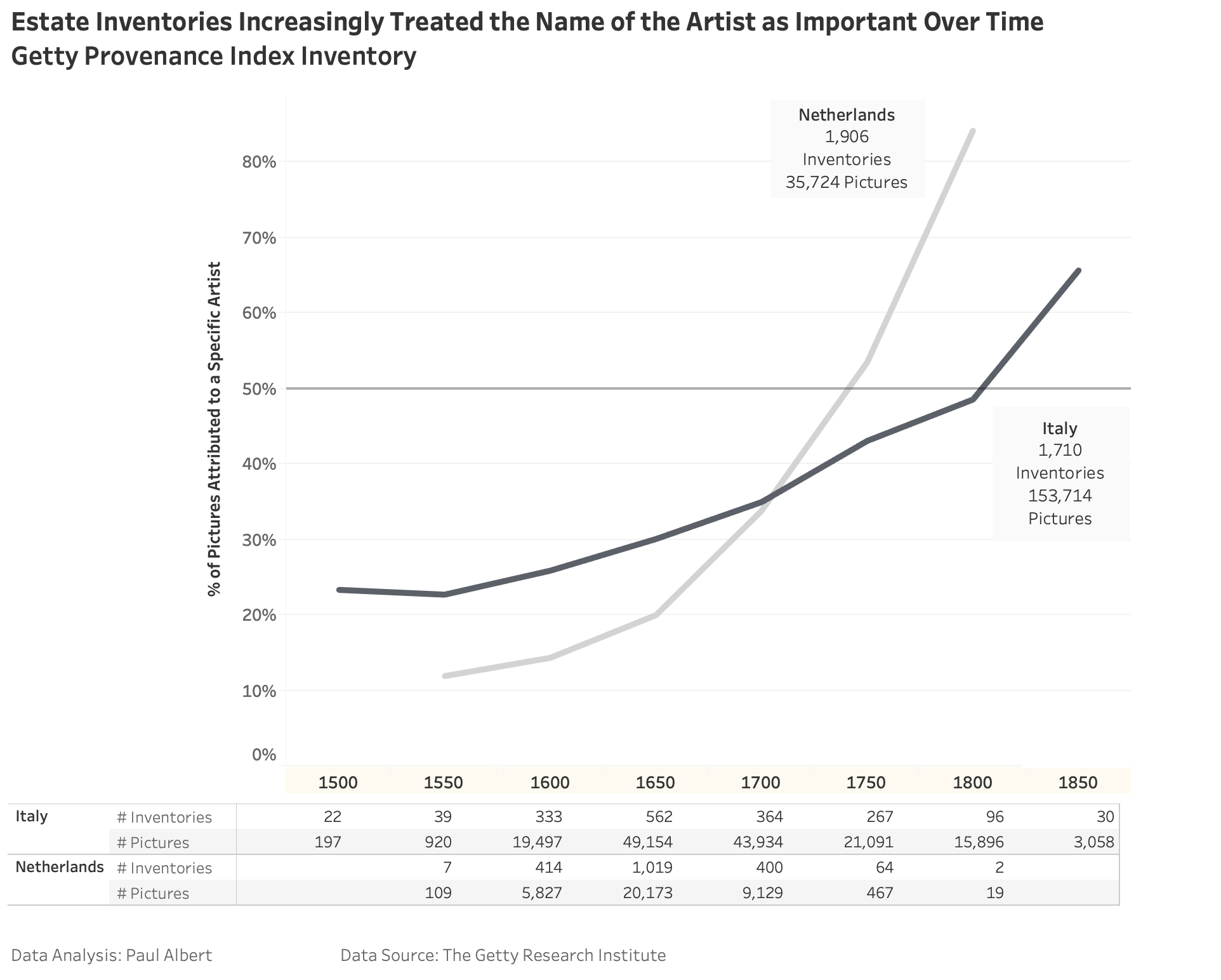

As well, personal inventories that had more often focused on describing the size of a picture or the gilding of the frame around it in the 1500’s, began also ascribing to pictures to particular artists. These personal inventories were most often created as legal purposes for the settling of estates (by death or marriage). Over 4,000 of these historic documents have been transcribed line by line by the Getty Research Institute as part of its Getty Provenance Index Database project.[34] This is an ongoing research initiative that has been operating for over 35 years.

As an original contribution, this paper offers the first known attempt to analyze this shift in inventory practices. What is important to note is that these inventories were lists describing objects (many of which might have been lost by history and, if they actually survived, cannot be tied to a specific inventory entry today). It is largely unknown if pictures ascribed to artists were actually done by that artist or even had a signature.

Regardless of whether a picture was actually signed, what is clear, however, is that there was a definite movement to attribute the name of an artist in describing an inventoried picture. This movement reflects a cultural shift in putting more importance on the name of the artist.

Figure 3. This chart reflects findings based on the Getty Research Institute’s Provenance Index, an ongoing 35-year old effort transcribing the contents of thousands of historical household inventories. In transcribing these inventories line by line, Getty experts identified listing entries for pictures (paintings, sketches, prints) where the artist was explicitly identified by the inventory entry.

Grouped by year of inventory, the data does suggest a shift in the historical importance in the wish to name artists by the people creating these inventories. It also might highlight differences between protestant and catholic countries in considering the name of the artist as important.

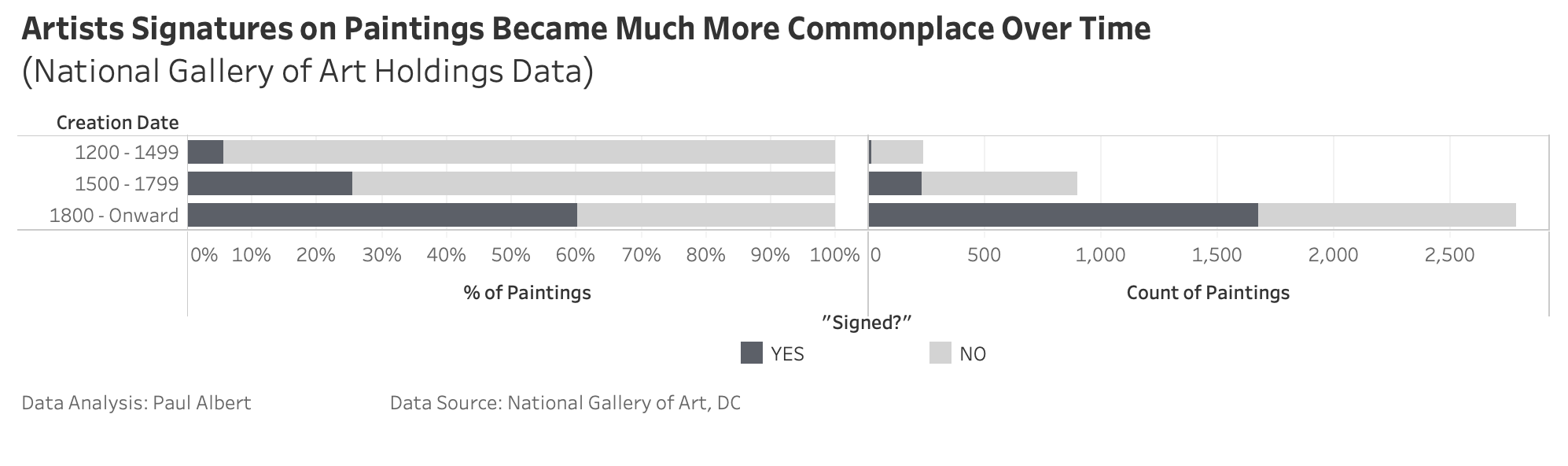

While the Getty data reflects the growing importance of the name of the artist to the person creating an estate inventory by the year of inventory, we can also ask if the practice of signing paintings became more prevalent over time by year of creation. Based on data provided to me by the National Gallery of Art (which does track in its inventory database if a work was signed by signature or artist emblem), we can see that artists more often directly signed their work over time.

Figure 4. For the purposes of this project, and as an original scholarly contribution, data was obtained from the National Gallery of Art examining their complete painting holdings.

Admittedly, this data has some limitations. Many of the earliest works in the National Gallery of Art’s (NGA) are pieces of a greater composition (e.g., a single panel of a triptych) that might have been signed and it can be questioned how well signature patterns in the holdings of the NGA by creation date actually represents the overall historical practices artists by the period in which they worked.

What is surprising, however, is that the practice of signing a painting was not nearly as universal as one might think. For example, of the 36 paintings completed since the year 2000 in the NGA’s holdings, at least a quarter of the paintings were not signed by the artist.

Conclusion

This paper examined the journey of the painter and sculptor from “artisan” to “Artists.” In this journey, it was not the physicality of the objects they produced that dramatically changed, it was how the nature of the objects they produced were thought of. It is a journey not just marked by one profession’s attempt to distinguish themselves from other professions, it is also a journey propelled by how the collectors and appreciators of their work tried to distinguish themselves from others.

This is a journey that continues.

Bibliography

Alpers, Svetlana Leontief. “Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari’s Lives.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 23, no. 3/4 (1960): 190–215. https://doi.org/10.2307/750591.

Bohn, Babette, and James M. Saslow. A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

Clifton, James. “Vasari on Competition.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 1 (1996): 23–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/2544267.

Gilbert, Creighton E. “What Did the Renaissance Patron Buy?” Renaissance Quarterly 51, no. 2 (1998): 392–450. https://doi.org/10.2307/2901572.

Goldstein, Carl. “Rhetoric and Art History in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque.” The Art Bulletin 73, no. 4 (1991): 641–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045834.

Goldwaite, Richard A. “The Painting Industry in Early Modern Italy.” In Painting for Profit. Yale University Press, 2010.

Heinich, Nathalie. Glory of Van Gogh: An Anthropology of Admiration. Text is Free of Markings edition. Princeton Univ. Press, 1996.

Jack, Mary Ann. “The Accademia Del Disegno in Late Renaissance Florence.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 7, no. 2 (1976): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539556.

Koppl, Roger, Stuart Kauffman, Teppo Felin, and Giuseppe Longo. “Economics for a Creative World.” Journal of Institutional Economics 11, no. 1 (March 2015): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137414000150.

Kris, Ernst, and Otto Kurz. Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist: A Historical Experiment. Yale University Press, 1981.

Michael. Baxandall. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.

Patrizia. Cavazzini. Painting as Business in Early Seventeenth-Century Rome. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008.

Shiner, Larry. The Invention of Art: A Cultural History. 51532nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Soussloff, Catherine M. The Absolute Artist: The Historiography of a Concept. U of Minnesota Press, 1997.

“The Getty Provenance Index.” Accessed October 23, 2018. http://piprod.getty.edu/starweb/pi/servlet.starweb?path=pi/pi.web.

Wittkower, Rudolf, and Margot Wittkower. Born Under Saturn: The Character and Conduct of Artists : A Documented History from Antiquity to the French Revolution. New York Review of Books, 2007.

Wolterstorff, Nicholas. Art Rethought: The Social Practices of Art. OUP Oxford, 2015.

-

Bohn and Saslow, A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art, 178. ↑

-

Clifton, “Vasari on Competition,” 41. ↑

-

Goldstein, “Rhetoric and Art History in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque,” 646. ↑

-

Soussloff, The Absolute Artist, 46. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 43–44. ↑

-

Shiner, 64. ↑

-

Jack, “The Accademia Del Disegno in Late Renaissance Florence,” 6. ↑

-

Michael. Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, 1. ↑

-

Gilbert, “What Did the Renaissance Patron Buy?,” 414. ↑

-

Koppl et al., “Economics for a Creative World,” 17. ↑

-

Wittkower and Wittkower, Born Under Saturn, 63. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 47. ↑

-

Alpers, “Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari’s Lives,” 190. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 58. ↑

-

Alpers, “Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari’s Lives,” 193. ↑

-

Goldwaite, “The Painting Industry in Early Modern Italy,” 288. ↑

-

Heinich, Glory of Van Gogh. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 85. ↑

-

Wolterstorff, Art Rethought, 23. ↑

-

Wolterstorff, 24. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 58. ↑

-

Shiner, 171. ↑

-

Shiner, 61. ↑

-

Shiner, 107. ↑

-

Shiner, 105. ↑

-

Bohn and Saslow, A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art, 39. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 116. ↑

-

Shiner, 135. ↑

-

Jack, “The Accademia Del Disegno in Late Renaissance Florence,” 9. ↑

-

Patrizia. Cavazzini, Painting as Business in Early Seventeenth-Century Rome, 61. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 84. ↑

-

Kris and Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist, 4. ↑

-

Shiner, The Invention of Art, 103. ↑

-

“The Getty Provenance Index.” ↑