Paul Albert

12/5/18

When bankers get together, they discuss art.

When artists get together, they discuss money.

Oscar Wilde

Setting the Stage

While the history of art is replete with stories of talented artists dying unknown and penniless, it is worthwhile to ask, “how did other roughly equivalently talented artists gain fame and fortune in their lifetimes?”. For, I believe, that if one were to ask any artist which they would prefer, living poor and unknown or living rich and famous, they all would state a preference for the latter.[1] Like as with you and me, artists can only aspire for posterity, but, day to day, actually measure their own worth and put bread on their table by how their efforts are recognized in their lifetime.

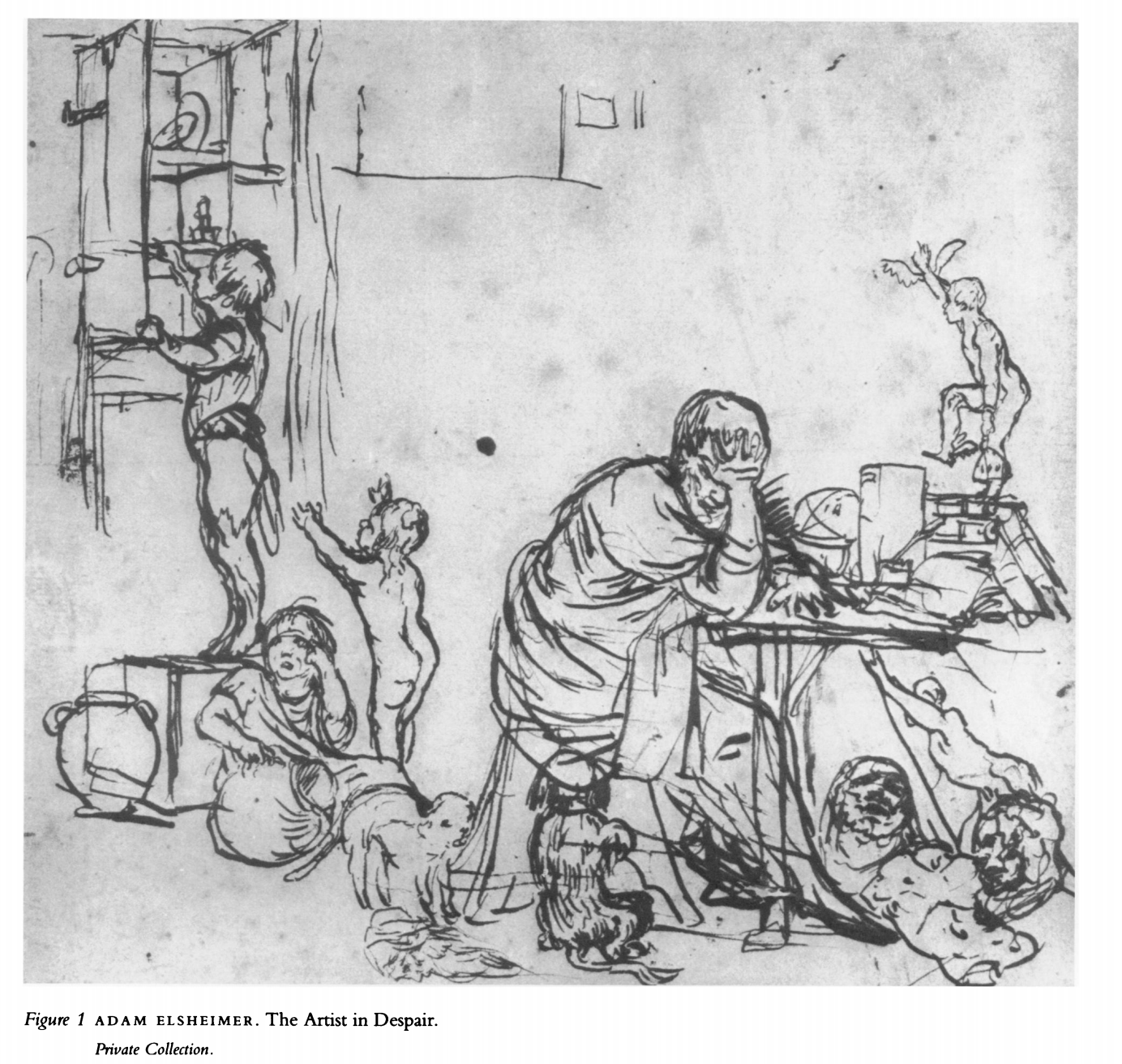

Figure 1. The Artist in Despair, Adam Elsheimer, Rome, circa 1600

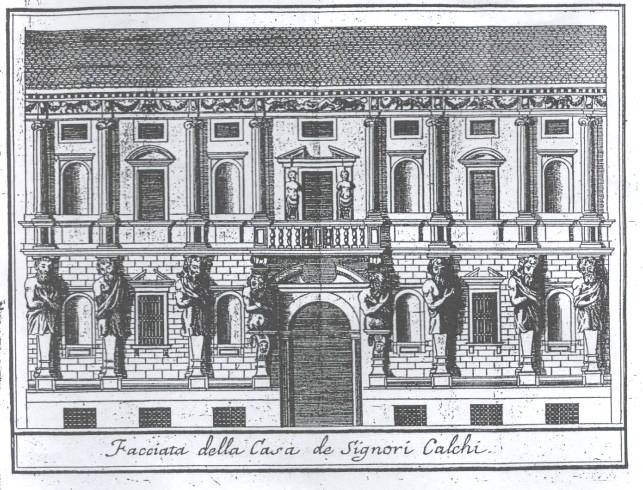

In 1556, Giorgio Vasari visited the house of the sculptor Leone Leoni in Milan.[2] Ten years later, Vasari wrote about Leoni’s opulent lifestyle and noted that “were Michelangelo to return to life… he would say that the art that caused him to be considered exceptional had become another thing” because artists now lived as princes.[3]

Figure 2. Casa degli Omenoni, Milan, Leone Leoni, 1562

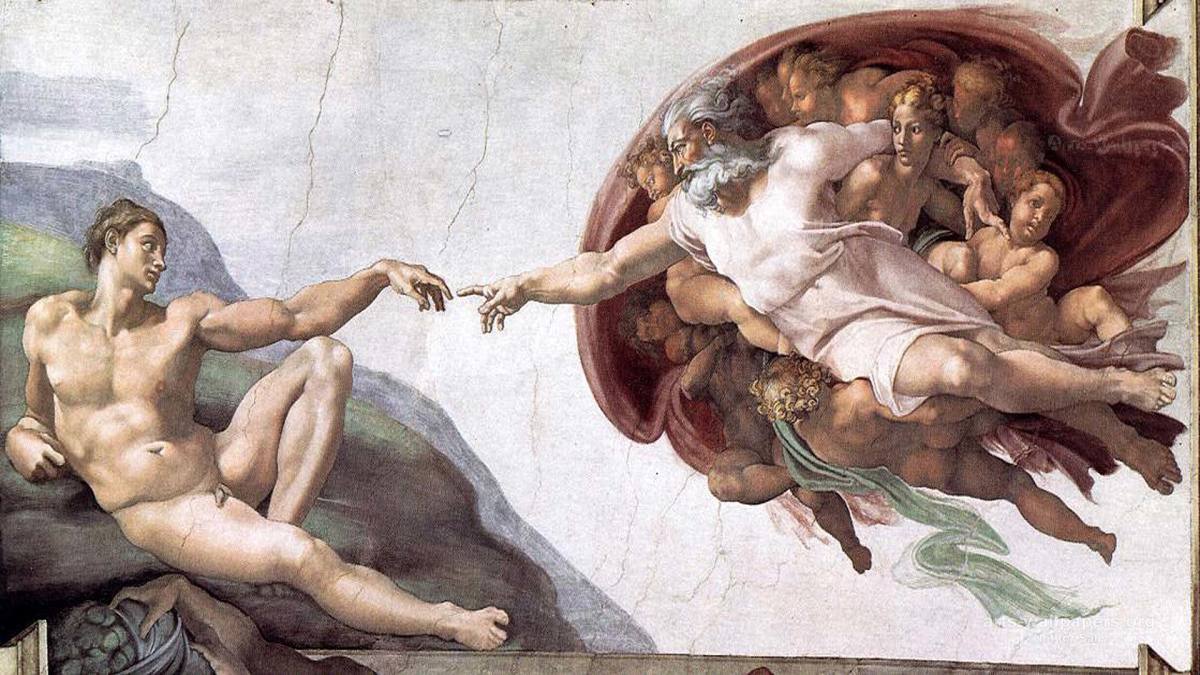

In contrast, Michelangelo lived a much less opulent lifestyle than Leoni and was known constantly complain about being poor. [4] Despite living in relatively conditions, when Michelangelo died in 1564, he left more liquid wealth behind than it cost the Medici family to purchase the Pitti Palace 15 years earlier.[5]

Figure 3. Pitti Palace, Florence, 1548

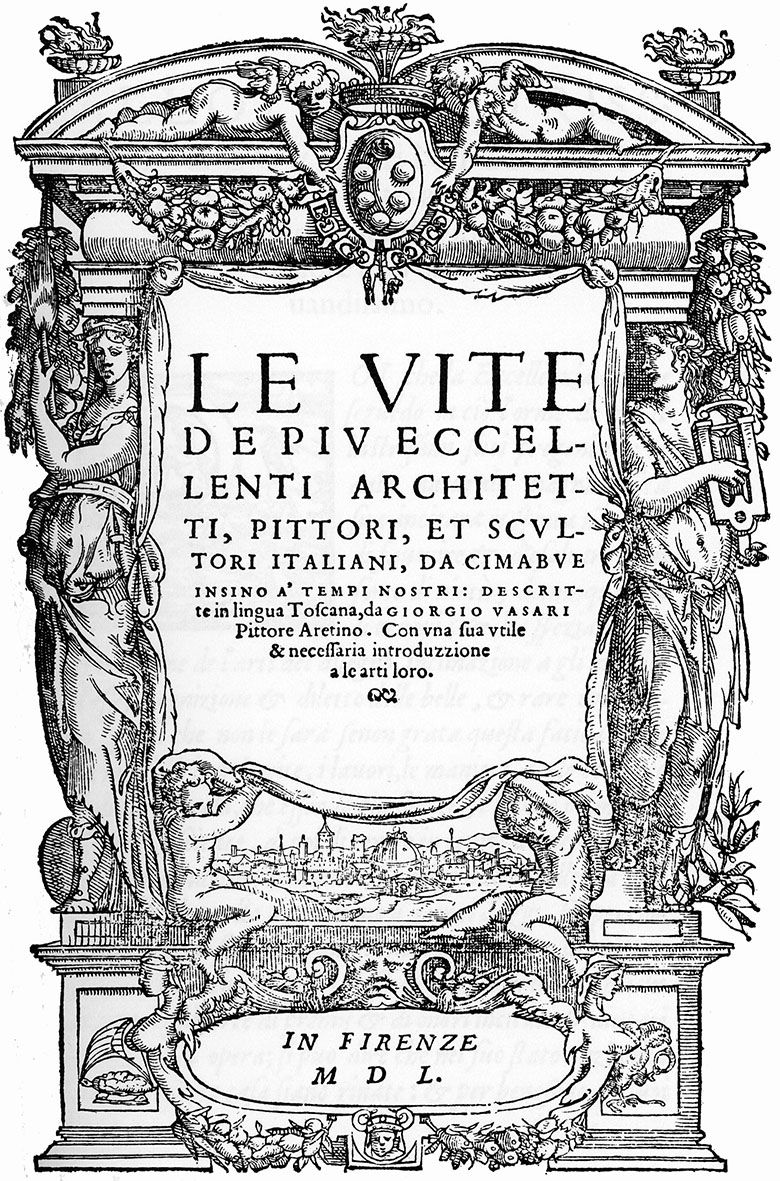

To start our historiographical investigation into what makes success in the artist’s life, I’d like to begin with writings of Georgio Vasari, which form a foundational cornerstones of modern western art history. In his Lives of the Artists (Vite), first published in 1550 and revised in 1568, Vasari devotes the bulk of the book discussing the lives of 250 artists and their work. Ernst Gombrich calls the Vite “perhaps the most famous and, even today, the most read work of the older literature of art” and notes “even today art history remains under his spell”[6]

In discussing the Vite, it is important to note that it does not seek to be mostly a work of history or a work mostly about a theory of art.[7] The Vite contains a few sections in which Vasari introduces overarching themes, but the bulk of the Vite are stories about individual artists and their works. It is a book that is meant to be pedagogical[8] about how an artist should live as well as theoretical in how art has developed. In his pedagogic stories, Vasari might make an aside to us, the reader, or he might have one of his characters make a point he wishes us to know.

What Vasari engages in the Vite is known as “common-sense talk,”[9] where aphorisms are put forward that can often disagree with each other, much as proverbs from the bible. As example, using aphorisms not found in the Vite, an aphorism such as “absence may make the heart grow fonder” might be made at one point, but the statement “out of sight, out of mind” might be made at a different point. In addition, Vasari, like his fellow humanist colleagues in the early modern age, also heavily borrowed terms and rhetorical conventions from the ancients. The result is that sometimes we are not able to tell if what Vasari is telling us is more formula than fact. In speaking about a humanist writer in Vasari’s time, Michael Baxandall notes “It is true that he would hardly have said these things if he had thought them obviously untrue, but they are something less than propositions springing direct from experience.”[10]

Given that the Vite was never intended to be a historical work as we know one and sometimes rhetorical formula might overshadow facts as known to Vasari, any attempt to gain fine-grain insight into Vasari’s thought needs to be tempered with a high degree of caution. With these caution klaxons ringing in our ears, let us now ask “what are the ingredients that lead to riches in artists’ lives in the Vasari’s Lives of the Artists?”

To begin, Vasari wants us to think that while many artists are poor,[11] it makes for a poor artist if she above all else seeks to become rich. Vasari writes:

And to tell the truth, those artists rarely succeed in being excellent whose final and principal aim is gain and profit not glory and honor, even if they have admirable talent. (Life of Rustici)[12]

Vasari, like the artist/historian Leon Battista Alberti a century before,[13] argues that a lust for money inhibits the artist to express herself with freedom and therefore inevitably results in a stunted product. He proposes instead that the artist should begin by seeking both glory and honor and that riches will likely follow.[14] Fittingly, this very proposition is echoed in the conception and gestation of the Vite itself. In 1647, Paoli Giovi, a friend of Vasari, wrote to Vasari to encourage Vasari’s efforts on the Vite. Giovi suggests that the work will bring Vasari fame and riches and notes that “gain comes from praise, but praise does not come from gain.”[15]

While Vasari is clear that money should not be the guiding ambition for the artist, he also wants us to believe that a lack of money and just rewards is injurious to art in general and the artist in particular.

It may be believed and therefore affirmed that, if just remuneration existed in our century, even greater and better works than the ancients ever executed would, without a doubt, he created. But being forced to struggle more with Hunger than with Fame, impoverished geniuses are buried and unable to earn a reputation (which is a shame and a disgrace for those who might be able to help them but take no care to do so). (Preface to Part Three)[16]

Beyond wealth, then, what would have constituted success during the life of an artist for Vasari? I believe he would have said technical/aesthetic excellence, ingenuity, virtue, honor and fame. But for Vasari, there is no absolute formula that will guarantee success. Rather than suggest an absolute path for success, Vasari seeks to understand what environmental conditions that might lead to success. One of those critical conditions is the artistic competition. That the artist be aware of and strive to surpass her past and present peers’ technical achievements.

Donald Preziosi, in highlighting this dynamic, notes that Vasari’s Vite

…constituted a systematic attempt to account for the apparent contradictions in the relativity of artistic reputation—the fact that artists could be considered justly great at a particular time and place even though their accomplishments might be seen by later generations, and with equal justification, as less great or as artistically incomplete.[17]

Preziosi points to these words from Vasari from the Preface to Part One of the Vite to support this point.

As the men of the age were not accustomed to see any excellence or greater perfection than the things thus produced, they greatly admired them, and considered them to be the type of perfection, barbarous as they were.

While Vasari states that artistic achievement can be measured by a scale set by the efforts of past and present achievements,[18] Vasari does not suggest that all is relative when it comes to what make great art. Indeed, an artist’s success is also the result of divine providence. By example, we can look at the artist Vasari considers to be the most successful and perfect artist of all time – Michelangelo.

In describing the birth of Michelangelo, the exemplar of the great artist, Vasari in his 1568 Vite writes that

There was born a son, … to Lodovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni…near the Sasso della Vernia, where S. Francis received the Stigmata… which son he gave the name Michelagnolo … inspired by some influence from above… he wished to suggest that he was something celestial and divine…[19]

Figure 4. Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo 1508-1512

In this passage, Vasari tells us that Michelangelo’s father was divinely inspired by God to choose the name Michelangelo for his son. A name that literally means “messenger who resembles God.”[20]

Vasari’s writings not only point to an extra-worldly nature for Michelangelo at birth[21], his writings also point to a heavenly nature in death. As with the legends of saints[22] that Vasari would have had heard countless times, Vasari records that after Michelangelo’s death, and his body laid in a coffin for twenty-two days, “we found it so perfect in every part, and so free from any noisome odor…as if he had passed away but a few hours before.”[23]

Nor was Michelangelo the only artist Vasari attributed divine providence to, Cimabue, Giotto and Leonardo, among others, enjoy that distinction as well. While Vasari certainly looked to the ancients as an exemplar for the Vite, it would be hard to suggest that his use of the term “divine” was merely formulaic. Indeed, Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz state that Vasari so often correlates the hand of the artist with the hand of God and proposed that the Vite is as much a theological work as a historical work.[24]

In Vasari’s theology, divine providence might play a part in an artist’s success, but it does not determine the artist’s success. Rather than relying on some form of predeterminism, Vasari’s grants artists a freedom of agency to use their talents to gain fame and its consequent riches or to act without virtue and never attain fame. To Vasari, while talent might be divinely planted, the fruits gained from this talent depend on a soil enriched by the virtuous efforts of the artist.[25]

However, there is more than virtue and hard work that leads to success. Lurking in the background of the Vite’s theology is also the idea that fortune, chance, plays a role in artistic success. Machiavelli’s Prince, preceding the Vite by about 35 years, explicitly writes that one half of person’s achievements can be attributed to fortune and one half can be attributed to virtú.[26] While Vasari does not offer such a definitive formula for the role of chance, fortune undoubtedly plays an important role in the Vasari’s core conceptions of artistic success.

Consider the frontispiece of the 1550 Lives shown in Figure X:

Figure 5. Title page of first version of Vasari Lives, 1550

On this prefatory page, we see many of the themes contained in the Vite. The Vite’s civic chauvinism is displayed in portraying the city of Florence, where god saw fit to provide the soil for the Renaissance, and the Medici crest reflecting whom the book is dedicated to is displayed on top. On the right we see Apollo looking to the left at Fame, who is holding a torch. On the plinth upon which Fame is supported is a ship with full sails sitting on top of a turtle. This device is not only a reference to Cosimo I[27] the duke to whom the Vite is dedicated to, it is also can serve as a reminder of good fortune, which is also frequently portrayed as a boat with full sails.[28]

In general, rather than positing fortune as a force that leads to fame, Vasari and his contemporaries tended to portray fortune more as a condition that needed to be conquered in order to achieve fame.[29],[30] This idea that the vicissitudes of fortune are a force that needs to conquered is beautifully illustrated by Vasari in the ceiling fresco that he completed by 1548 for his own house in Arezzo.

Figure 6. Virtue struggling with Fortune and Envy, Giorgio Vasari, Casa da Vasari, Arezzo, 1548

Vasari wrote that in the ceiling to this room dedicated to the theme of Fortune:

I did … a large painting in the middle, that contains life-size figures of Virtue with Envy, under her feet, and Fortune, gripped by the hair, while she beats both. A circumstance that gave great pleasure then is that in going round the room Fortune at one place seems above Envy and Virtue, and at another Virtue is above Envy and Fortune, just as it is often the case in reality.[31]

This opportunity to see Virtue triumphing over Fortune and Fortune triumphing over Virtue in equal measure as one walks around the room visually echoes Machiavelli’s earlier written suggestion that Fortune and Virtue have equal contributions to a person’s achievements.[32] Significantly, by having Virtue hold onto a lock of Fortune’s hair, Vasari also suggests that Fortune can sometimes bring a favorable wind, and when that happens, one needed to grasp and use the force of good fortune.

In the case of the artist Pinturicchio, Vasari notes

Just as there are many aided by Fortune who have not been endowed with much talent, so, on the contrary, there are countless talented men persecuted by adverse and hostile Fortune. Thus, it is common knowledge that Fortune adopts as her children those who depend upon her without the help of any talent, for she likes to raise up some with her own favour who would never have been recognized through their own worth. This is what happened with Pinturicchio from Perugia, who, even though he executed many works and was assisted by various people, none the less enjoyed a much greater reputation than his works deserved.[33]

The Standing Ovation Model

To further investigate Vasari thoughts on success in artist’s lives, I’d like us to think about a conceptual model that social theorists call the Standing Ovation Problem.[34] In this model, we are in a theater where a performance has just ended and asked if the performance will be given a standing ovation. For the sake of our analysis let us equate a standing ovation with fame and riches in an artist’s life.

I suggest that Vasari argues that it is the quality of the performance itself that determines whether a standing ovation will be awarded. That each actor’s performance is based on the artist’s competition with the other artists on stage that night as well as with other artists whose performances from the past they have seen. Indeed, as previously noted, Vasari sees this form of referential competition as a vital and indispensable force that furthers the history of art and nurtures artistic progress.[35],[36]

Based on his historic mindset and essentialist aesthetic[37], I doubt that Vasari would fully embrace the idea that the audience for the performance also acts in such a self-referential way. As already noted, Vasari would be willing to say the audience measures quality based on the performances they have seen. But beyond this principal, it is key to note that while performers compete with each other in Vasari’s writings, Vasari does not offer audience members the ability to cooperate with each other in deciding whether to give a performance a standing ovation. To Vasari’s the artists are given more freedom and agency to interact in more complex ways than is granted the audience.

Vasari’s almost sole focus on the performer in his seminal writings resulted in a focus that dramatically tilted the biases of art historians for centuries afterward to look more to the performer than the audience in explaining artistic success. Catherine Soussloff observes:

Abby Warburg recognized the reliance of art historians on this primary literature that he criticized. He said that “our ordinary, enthusiastic, biographically orientated history of art” comes from Renaissance biographies by Vasari and others, resulting in a reliance on individual genius and “hero-worship” that he saw as particularly “peculiar to the propertied classes, the collector and his circle.[38]

I suggest that that the degree of focus on the artist as myth has introduced a bias into art history, a bias that has prevented us from a more full and nuanced understanding of what leads to artist success. Pierre Bourdieu notes:

The ’charisma’ ideology … is undoubtedly the main obstacle to a rigorous science of the production of the value of cultural goods. It is this ideology which directs attention to the apparent producer, the painter, writer or composer, in short, the ’author’, suppressing the question of what authorizes the author… The question can be asked in its most concrete form: who is the true producer of the value of the work – the painter or the dealer? [39]

In short, what makes reputations is not . . . this or that ‘influential’ person, this or that institution, review, magazine, academy, coterie, dealer or publisher; it is not even the whole set of what are sometimes called ‘personalities of the world of arts and letters’; it is the field of production, understood as the system of objective relations between these agents or institutions and as the site of the struggles for the monopoly of the power to consecrate, in which the value of works of art and belief in that value are continuously generated.[40]

Bourdieu goes on to brilliantly summarize this messy and self-referential process as “social alchemy.” Elizabeth Honig describes a very similar dynamic to Bourdieu’s operating in early modern Europe.

This second site of value-creation, which I will call the honor system … comes to encompass forms of discourse that evolvè in the Renaissance to validate the status of the artist, but it also incorporates complex modes of social behavior that are in themselves means of negotiating status. The objects that circulate in this system cannot and indeed must not be translatable into a purely monetary value, for they are signifiers of power, honor, and obligation to those who exchange them.[41]

Against the proposition that it is hero-artists work itself that primarily accounts for artistic success, contemporary social theorists suggest that it is instead, other people influencing each other. The sociologist Duncan Watts notes:

…social epidemics require just the right conditions to be satisfied by the network of influence. And as it turned out, the most important condition had nothing to do with a few highly influential individuals at all. Rather, it depended on the existence of a critical mass of easily influenced people who influence other easy-to-influence people. When this critical mass existed, even an average individual was capable of triggering a large cascade—just as any spark will suffice to trigger a large forest fire when the conditions are primed for it.[42]

Challenges to Narrating Success

To further understand how the narrative approach and implied causalities of Vasari’s Vite might impose a bias that posits artistic success as mainly a property of the performance, it is useful to contrast the findings of other scholars examining the phenomenon of success as a social outcome.

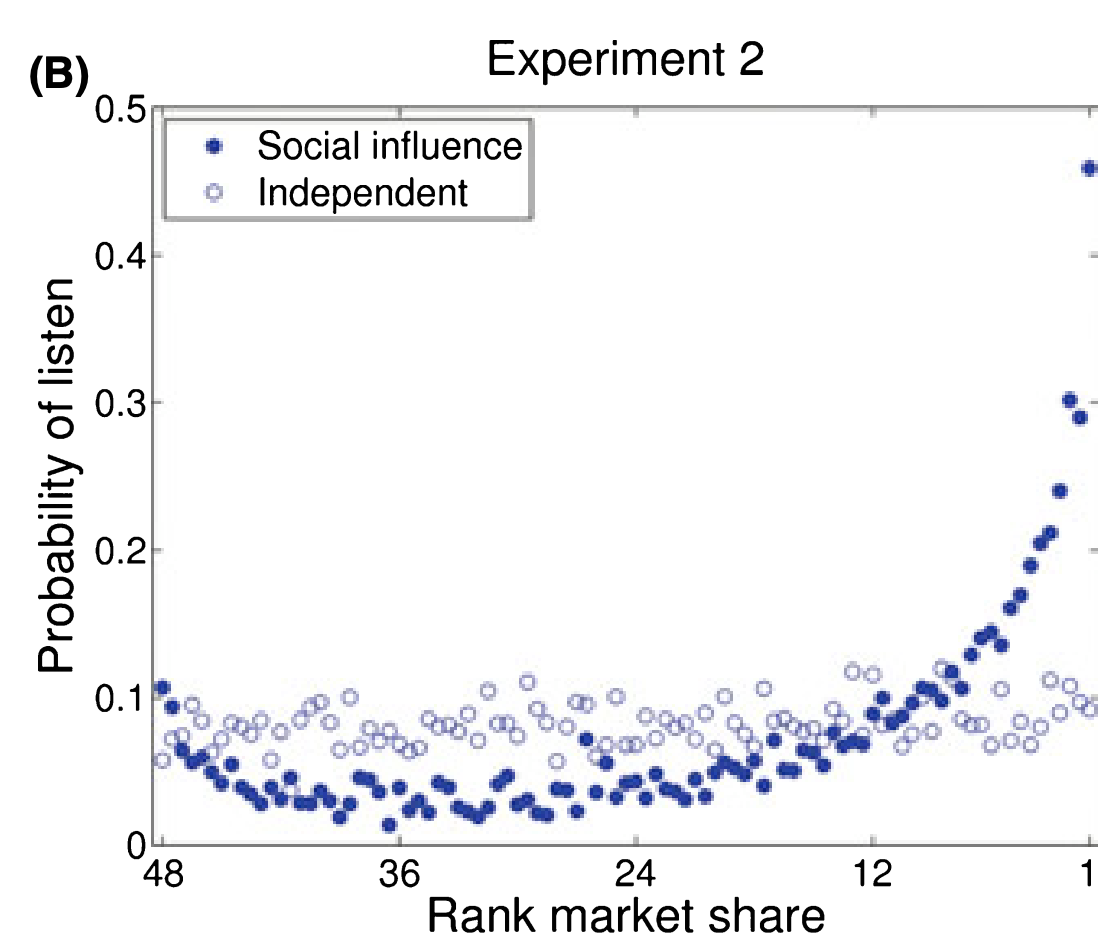

Duncan Watts, in a series of experiments, created a number of online “worlds” that he populated with different audiences, with over 14,000 subjects in total.[43] He asked each of the audiences to listen to and rate songs and then displayed an updated average rating for each song. What he found at the end of the experiment was that the best rated songs in each of the worlds greatly diverged from each other (as well as from a control world where the audience was asked to rate songs but did not see what each other’s ratings were). For example, a song that was ranked number one in one world, was ranked 40th in another world.[44] Watt’s conclusion is that allowing his audience to see each other’s ratings introduces a measure of randomness based on the order in which each member rates each song.[45] That if the experiment were run over again with the exact same audience and the exact same songs for the exact same worlds, the outcomes in each world would vary wildly if the order in which each audience member rated the song were changed. Artistic success is dependent on the path of how the artist perceptions are shared by the audience.[46]

Figure 7. When subjects saw other subjects ratings of songs, they were much more likely to listen to the better rated songs.

Watt’s findings, that shared audience opinion is not just shaped by the artist’s performance, but also by the order in which opinions are shared offers a valuable methodological insight for art historians. It calls for the historian to not just look at patron/artist itself, but also how patrons related to other patrons and society at large.

In other work that this author has done, the self-referentiality of the audience in determining artistic success was further highlighted. Using a Getty Institute database of prices paid during the 17th century in Rome by patrons directly to artists, I found that artist career earnings were much more impacted by the unique number of patrons the artist captured than the sheer number of commissions gained or even the number of years the artist worked.[47]

This finding suggests that that “Artists carry with them in their prestige package a history of past relationships…. Present-day status is based on a position within a web of ties and also has embedded within it the history of past positions.”[48] At least in 17th century Rome, career rewards to an artist’s monetary value lay in their ability to bridge and connect patron networks to each other.

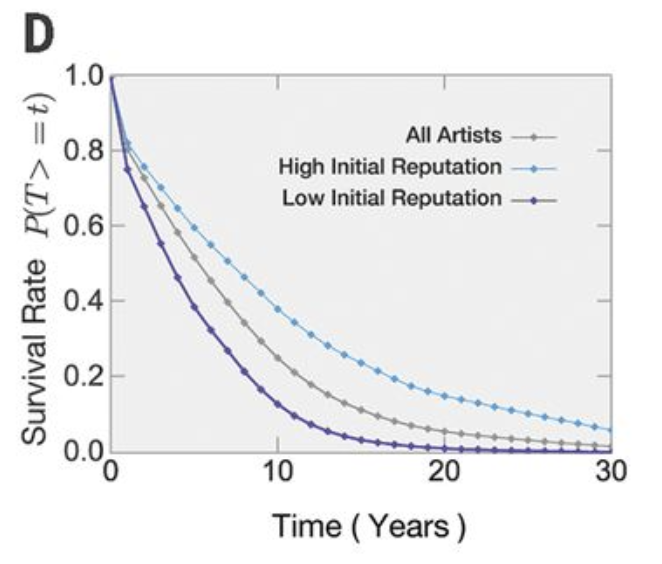

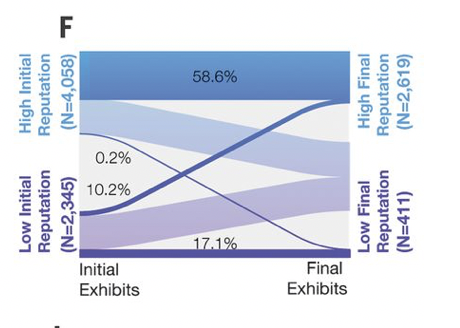

In a recently published study by Samuel Frailberger, et.al, the career trajectories of about one-half million artists across twenty-three thousand institutions over 26 years were examined.[49] The findings dramatically highlight the idea of path dependence, that where an artist starts their career has a dramatic impact on career success. For example, artists that began exhibiting in low prestige galleries showed a much greater likelihood of dropping out of the market. Artist that began their careers with high prestige galleries are much more likely to maintain showing at high prestige galleries.

Figure . Artists beginning with more prestigious showings less likely to drop out of art market

Figure 9. Artist beginning with more prestigious showings much more likely to end with prestigious showings.

Self-Referentiality as Art

In 1970, the artist Hans Haacke created a pioneering art exhibit that exactly highlights the nature of audience self-referentiality in art.[50] Visitors were encouraged to interact with a computer keyboard, very much a novelty at the time, and enter data about themselves such as age, gender and opinions on matters such as whether marijuana use should be punished. Their answers were instantly tabulated and shown on a large screen on the wall of the installation. According to Haacke, “the visitors, in effect, were producing a collective self-portrait in a participatory and self-reflective process.”[51]

This paper argues that exactly this dynamic that underlies artistic success. It is not just the work of the artist that drives success, success is, instead, the product of its reception. As Albert-László Barabási summarizes:

Your success isn’t about you and your performance.

It’s about us and how we perceive your performance.

Or, to put it simply, your success is not about you, it’s about us.[52]

Bibliography

Albert, Paul. “Art Market Dynamics in Seicento Rome.” Accessed December 3, 2018. http://visualhumanist.com/academic/81/.

Alberti, Leon Battista, and Cecil Grayson. On Painting and On Sculpture: The Latin Texts of De Pictura and De Statua. Phaidon, 1972.

Barabási, Albert-László. The Formula: The Universal Laws of Success. Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

Barolsky, Paul. “The Theology of Vasari.” Notes in the History of Art 19, no. 3 (2000): 1–6.

———. “What Are We Reading When We Read Vasari?” Notes in the History of Art 22, no. 1 (2002): 33–35.

Billig, Michael. Arguing and Thinking: A Rhetorical Approach to Social Psychology. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Bonus, Holger, and Dieter Ronte. “Credibility and Economic Value in the Visual Arts.” Journal of Cultural Economics 21, no. 2 (June 1, 1997): 103–18. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007338319088.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Columbia University Press, 1993.

Bull, George. “Popes, Princes and Peasants: The Diversity of Patronage in Vasari’s ‘Lives.’” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 135, no. 5370 (1987): 419–29.

Cheney, Liana De Girolami. Giorgio Vasari’s Teachers: Sacred & Profane Art. Peter Lang, 2007.

———. The Homes of Giorgio Vasari. Peter Lang, 2006.

Cioffari, Vincenzo. “The Function of Fortune in Dante, Boccaccio and Machiavelli.” Italica 24, no. 1 (1947): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/476522.

Cuneo, Pia F. Artful Armies, Beautiful Battles: Art and Warfare in the Early Modern Europe. Brill, 2002.

Deborah Cibelli. “Images of Fame and Changing Fortune in the First and Second Editions of Vasari’s ‘Vite.’” Explorations in Renaissance Culture 25, no. 1 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1163/23526963-90000207.

Delancey, Julia. Review of The Wealth of Michelangelo, by Rab Hatfield. Renaissance Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2004): 207–9.

Elizabeth Honig. “The Artist: Homo Economicus/ Femina Economica.” In A History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and Markets, edited by Titia Hulst. Univ of California Press, 2017.

Fraiberger, Samuel P., Roberta Sinatra, Magnus Resch, Christoph Riedl, and Albert-László Barabási. “Quantifying Reputation and Success in Art.” Science, November 8, 2018, eaau7224. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau7224.

Giuffre, Katherine. “Sandpiles of Opportunity: Success in the Art World.” Social Forces 77, no. 3 (1999): 815–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3005962.

Goldstein, Carl. “Rhetoric and Art History in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque.” The Art Bulletin 73, no. 4 (1991): 641–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045834.

Gombrich, E. H., and Max Marmor. “The Literature of Art.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 11, no. 1 (1992): 3–8.

Kelley Helmstutter Di Dio. “Leone Leoni’s Signposting in Sixteenth-Century Milan.” In The Patron’s Payoff: Conspicuous Commissions in Italian Renaissance Art, edited by Jonathan K. Nelson and Richard J. Zeckhauser. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Kris, Ernst, and Otto Kurz. Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist: A Historical Experiment. Yale University Press, 1981.

Maginnis, Hayden B. J. “Matters of Money: Vasari on Early Italian Artists.” Notes in the History of Art 14, no. 1 (1994): 6–9.

Mezzatesta, Michael P. “The Façade of Leone Leoni’s House in Milan, the Casa Degli Omenoni: The Artist and the Public.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 44, no. 3 (1985): 233–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/990074.

Michael. Baxandall. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.

“Michelangelo (given Name).” Wikipedia, October 23, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Michelangelo_(given_name)&oldid=806590218.

Page, Scott. “The Standing Ovation Problem – Miller – 2004 -.” Complexity, 2004. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.mutex.gmu.edu/doi/abs/10.1002/cplx.20033.

Pon, Lisa. “Michelangelo’s Lives: Sixteenth-Century Books by Vasari, Condivi, and Others.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 4 (1996): 1015–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2543906.

Preziosi, Donald. The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Rubin, Patricia Lee, and Maurice Rubin. Giorgio Vasari: Art and History. Yale University Press, 1995.

Salganik, Matthew J., and Duncan J. Watts. “Web-Based Experiments for the Study of Collective Social Dynamics in Cultural Markets.” Topics in Cognitive Science 1, no. 3 (July 2009): 439–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01030.x.

Shanken, Edward A. “Investigatory Art: Real-Time Systems and Network Culture.” Accessed December 4, 2018. https://necsus-ejms.org/investigatory-art-real-time-systems-and-network-culture/.

Soussloff, Catherine M. The Absolute Artist: The Historiography of a Concept. U of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Spear, Richard E., Philip Sohm, Christopher R. Marshall, Raffaella Morselli, Elena Fumagalli, and Renata Ago. Painting for Profit: The Economic Lives of Seventeenth-Century Italian Painters. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2010.

Tate. “Hans Haacke; Lessons Learned, Landmark Exhibitions Issue, Tate Papers No.12 Autumn 2009.” Tate. Accessed December 4, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/12/lessons-learned.

Vasari, Giorgio. The Lives of the Artists. OUP Oxford, 1998.

Vasari, Giorgio, and Jean Paul Richter. Lives Of The Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, And Architects, Volume 4. Arkose Press, 2015.

Verstegen, Ian. “Vasari’s Progressive (but Non-Historicist) Renaissance.” Journal of Art Historiography; Glasgow, 2011. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1017601236/citation/35DC9B0A4E184CEEPQ/5.

Watts, Duncan J. Everything Is Obvious: Once You Know the Answer. Crown Publishing Group, 2011.

———. “Is Justin Timberlake a Product of Cumulative Advantage?” The New York Times, April 15, 2007, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/15/magazine/15wwlnidealab.t.html.

-

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (Columbia University Press, 1993), 79. ↑

-

Michael P. Mezzatesta, “The Façade of Leone Leoni’s House in Milan, the Casa Degli Omenoni: The Artist and the Public,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 44, no. 3 (1985): 233, https://doi.org/10.2307/990074. ↑

-

Kelley Helmstutter Di Dio, “Leone Leoni’s Signposting in Sixteenth-Century Milan,” in The Patron’s Payoff: Conspicuous Commissions in Italian Renaissance Art, ed. Jonathan K. Nelson and Richard J. Zeckhauser (Princeton University Press, 2014), 149. ↑

-

Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists (OUP Oxford, 1998), 475. ↑

-

Julia Delancey, review of The Wealth of Michelangelo, by Rab Hatfield, Renaissance Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2004): 208. ↑

-

E. H. Gombrich and Max Marmor, “The Literature of Art,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 11, no. 1 (1992): 5. ↑

-

Paul Barolsky, “What Are We Reading When We Read Vasari?,” Notes in the History of Art 22, no. 1 (2002): 33–35. ↑

-

Gombrich and Marmor, “The Literature of Art,” 5. ↑

-

Michael Billig, Arguing and Thinking: A Rhetorical Approach to Social Psychology (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 236. ↑

-

Carl Goldstein, “Rhetoric and Art History in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque,” The Art Bulletin 73, no. 4 (1991): 643, https://doi.org/10.2307/3045834. ↑

-

Richard E. Spear et al., Painting for Profit: The Economic Lives of Seventeenth-Century Italian Painters (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2010), 4. ↑

-

Patricia Lee Rubin and Maurice Rubin, Giorgio Vasari: Art and History (Yale University Press, 1995), 58. ↑

-

Leon Battista Alberti and Cecil Grayson, On Painting and On Sculpture: The Latin Texts of De Pictura and De Statua (Phaidon, 1972), 67. ↑

-

Hayden B. J. Maginnis, “Matters of Money: Vasari on Early Italian Artists,” Notes in the History of Art 14, no. 1 (1994): 7. ↑

-

Rubin and Rubin, Giorgio Vasari, 407. ↑

-

Giorgio Vasari and Jean Paul Richter, Lives Of The Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, And Architects, Volume 4 (Arkose Press, 2015), 283. ↑

-

Donald Preziosi, The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology (Oxford University Press, 2009), 15. ↑

-

Ian Verstegen, “Vasari’s Progressive (but Non-Historicist) Renaissance*,” Journal of Art Historiography; Glasgow, 2011, 4, http://search.proquest.com/docview/1017601236/citation/35DC9B0A4E184CEEPQ/5. ↑

-

Vasari and Richter, Lives Of The Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, And Architects, Volume 4, 341. ↑

-

“Michelangelo (given Name),” Wikipedia, October 23, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Michelangelo_(given_name)&oldid=806590218. ↑

-

Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist: A Historical Experiment (Yale University Press, 1981), 59. ↑

-

Lisa Pon, “Michelangelo’s Lives: Sixteenth-Century Books by Vasari, Condivi, and Others,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 4 (1996): 1022, https://doi.org/10.2307/2543906. ↑

-

Catherine M. Soussloff, The Absolute Artist: The Historiography of a Concept (U of Minnesota Press, 1997), 35–36. ↑

-

Paul Barolsky, “The Theology of Vasari,” Notes in the History of Art 19, no. 3 (2000): 1. ↑

-

Maginnis, “MATTERS OF MONEY,” 7–8. ↑

-

Vincenzo Cioffari, “The Function of Fortune in Dante, Boccaccio and Machiavelli,” Italica 24, no. 1 (1947): 10, https://doi.org/10.2307/476522. ↑

-

Liana De Girolami Cheney and Liana Cheney, Giorgio Vasari’s Teachers: Sacred & Profane Art (Peter Lang, 2007), 203. ↑

-

Deborah Cibelli, “Images of Fame and Changing Fortune in the First and Second Editions of Vasari’s ‘Vite,’” Explorations in Renaissance Culture 25, no. 1 (1999): 116, https://doi.org/10.1163/23526963-90000207. ↑

-

Deborah Cibelli, 117. ↑

-

Cioffari, “The Function of Fortune in Dante, Boccaccio and Machiavelli,” 4. ↑

-

Liana Cheney and Liana De Girolami Cheney, The Homes of Giorgio Vasari (Peter Lang, 2006), 137. ↑

-

Pia F. Cuneo, Artful Armies, Beautiful Battles: Art and Warfare in the Early Modern Europe (Brill, 2002), 232. ↑

-

Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, 250. ↑

-

“The Standing Ovation Problem – Miller – 2004 – Complexity – Wiley Online Library,” accessed December 3, 2018, https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.mutex.gmu.edu/doi/abs/10.1002/cplx.20033. ↑

-

George Bull, “Popes, Princes and Peasants: The Diversity of Patronage in Vasari’s ‘Lives,’” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 135, no. 5370 (1987): 421. ↑

-

Michael. Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), 26. ↑

-

Verstegen, “Vasari’s Progressive (but Non-Historicist) Renaissance*,” 7. ↑

-

Soussloff, The Absolute Artist, 87. ↑

-

Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production, 76. ↑

-

Bourdieu, 78. ↑

-

Elizabeth Honig, “The Artist: Homo Economicus/ Femina Economica,” in A History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and Markets, ed. Titia Hulst (Univ of California Press, 2017), 83. ↑

-

Duncan J. Watts, Everything Is Obvious: Once You Know the Answer (Crown Publishing Group, 2011), 96. ↑

-

Matthew J. Salganik and Duncan J. Watts, “Web-Based Experiments for the Study of Collective Social Dynamics in Cultural Markets,” Topics in Cognitive Science 1, no. 3 (July 2009): 439–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01030.x. ↑

-

Duncan J. Watts, “Is Justin Timberlake a Product of Cumulative Advantage?,” The New York Times, April 15, 2007, sec. Magazine, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/15/magazine/15wwlnidealab.t.html. ↑

-

Watts, Everything Is Obvious, 79. ↑

-

Holger Bonus and Dieter Ronte, “Credibility and Economic Value in the Visual Arts,” Journal of Cultural Economics 21, no. 2 (June 1, 1997): 210, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007338319088. ↑

-

Paul Albert, “Art Market Dynamics in Seicento Rome,” accessed December 3, 2018, http://visualhumanist.com/academic/81/. ↑

-

Katherine Giuffre, “Sandpiles of Opportunity: Success in the Art World,” Social Forces 77, no. 3 (1999): 818, https://doi.org/10.2307/3005962. ↑

-

Samuel P. Fraiberger et al., “Quantifying Reputation and Success in Art,” Science, November 8, 2018, eaau7224, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau7224. ↑

-

“Investigatory Art: Real-Time Systems and Network Culture,” accessed December 4, 2018, https://necsus-ejms.org/investigatory-art-real-time-systems-and-network-culture/. ↑

-

Tate, “Hans Haacke; Lessons Learned, Landmark Exhibitions Issue, Tate Papers No.12 Autumn 2009,” Tate, accessed December 4, 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/12/lessons-learned. ↑

-

Albert-László Barabási, The Formula: The Universal Laws of Success (Little, Brown and Company, 2018), 24. ↑